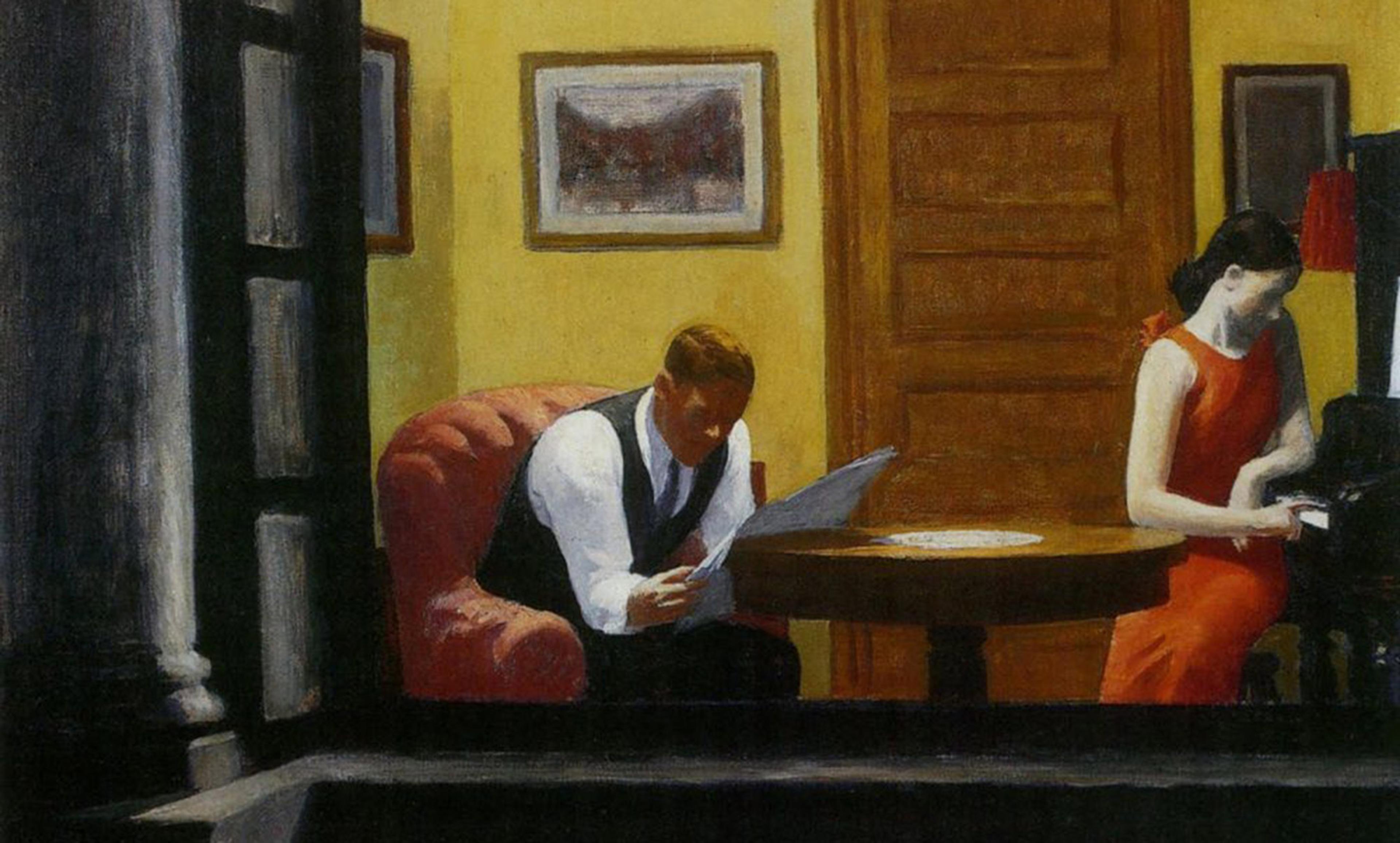

Phobia cured? Maybe not. Photo by GollyGForce/Flickr

Over the past decade, many scholars have questioned the credibility of research across a variety of scientific fields. Some of these concerns arise from cases of outright fraud or other misconduct. More troubling are difficulties in replicating previous research findings. Replication is cast as a cornerstone of science: we can trust the results originating in one lab only if other labs can follow similar procedures and get similar results. But in many areas of research – including psychology – scientists have found that too often they cannot replicate prior findings.

As psychologists specialising in clinical work (Alexander Williams) and methodology (John Sakaluk), we wondered what these concerns mean for psychotherapy. Over the past 50 years, therapy researchers have increasingly embraced the evidence-based practice movement. Just as medicines are pitted against placebos in research studies, psychologists have used randomised clinical trials to test whether certain therapies (eg, ‘exposure therapy’, or systematically confronting what one fears) benefit people with certain mental-health conditions (eg, a phobia of spiders). The treatment-for-diagnosis combinations that have amassed evidence from these trials are known as empirically supported treatments (ESTs).

We wondered, though: is the credibility of the evidence for ESTs as strong as that designation suggests? Or does the evidence-base for ESTs suffer from the same problems as published research in other areas of science? This is what we (with our coauthors, the US psychologists Robyn Kilshaw and Kathleen T Rhyner) explored in our study published recently in the Journal of Abnormal Psychology.

The Society of Clinical Psychology – or Division 12 of the American Psychological Association – has done the arduous work since the 1990s of establishing a list of more than 70 ESTs. They have continued to update the ESTs listed, and the evidence cited for them, to the present day. We conducted a ‘meta-scientific review’ of these ESTs. Across a variety of statistical metrics, we assessed the credibility of the evidence cited by the Society for every EST on their list. We examined measures related to statistical power, which indicates plausibility of the reported data given the sample sizes of the experiments. We computed Bayesian indices of evidence that shows how probable the results were, assuming the therapies actually helped those receiving them. We even looked at rates of misreported statistics – if a study reports, say, ‘2 + 2 = 5’, we know that there must be a problem with at least some of the numbers. All told, we analysed more than 450 research articles. What we found is a study in contrasts.

Around 20 per cent of ESTs performed well across a majority of our metrics (eg, problem-solving therapy for depression, interpersonal psychotherapy for bulimia nervosa, the aforementioned exposure therapy for specific phobias). This means not only that the therapies have been subjected to clinical trials, but that the evidence produced from these clinical trials seems credible and supports the claim that the EST will help people. We also found a ‘murky middle’: 30 per cent of ESTs had mixed results across metrics, performing neither consistently well nor poorly (eg, cognitive therapy for depression, interpersonal psychotherapy for binge-eating disorder).

That leaves 50 per cent of ESTs with subpar outcomes across most of our metrics (eg, eye-movement desensitisation and reprocessing for PTSD, interpersonal psychotherapy for depression). In other words, although these ESTs seemed to work based on the claims of the clinical trials cited by the Society of Clinical Psychology, we found the evidence from these trials lacked statistical credibility. For these ESTs, the relevant research results are sufficiently ambiguous that we cannot be sure that they really do work better than other forms of therapy.

There is a large, dense body of literature showing that psychotherapy usually helps those who seek it out. Our results don’t challenge that conclusion. What does it mean, though, if the evidence behind the therapies thought to be best supported by research is not as strong as one would hope?

One conclusion we draw is that we might be in need of what we’re calling ‘psychological reversal’. The term, a version of what the US medical scholars Vinay Prasad and Adam Cifu called medical reversal, argues for desisting from the use of psychological practices if they are found to be ineffective, inadvertently harmful or more expensive to employ than equally effective alternatives. If some ESTs lack credible evidence that they are superior to simpler, less costly and time-consuming forms of therapy, shifting resources towards the latter group of treatments will benefit therapy clients and all those bearing the costs of mental-health care.

The other conclusion is a lesson in humility for those who provide therapy (one of the authors of this article among them). For close to a century, psychologists have debated the ‘dodo bird hypothesis’. Deriving its name from the proclamation of the Dodo Bird in Alice in Wonderland (‘Everybody has won and all must have prizes!’), the dodo bird hypothesis suggests that different forms of psychotherapy perform equally well, and that this is because of the common factors of all therapies (eg, they all provide clients with a rationale for the therapy). The existence of ESTs seems to refute the hypothesis, demonstrating that some therapies do work better than others for certain mental-health conditions. We put forward a different possibility: the ‘don’t know’ bird hypothesis. Given the problems with credibility we found across many clinical trials, we contend that we currently don’t know in many cases if some therapies perform better than others. Of course, this also means we don’t know if the majority of therapies are equally effective, and, if such equality exists, we don’t know if it owes to common factors. When it comes to comparing psychotherapies, therapists could do worse than to channel every philosophy undergrad: when someone purports one therapy works better than another, wonder aloud: ‘How do we know?’

Psychotherapy could be on the verge of a renaissance. Research on mental-illness treatment can benefit greatly from the lessons psychology has learned about credibility. For example, investigators can ensure that their studies have sufficient power; that is, enough participants in a clinical trial to reliably detect if a psychotherapy works. They can also practise open science by making their datasets publicly available so that other researchers can verify that a trial’s statistics are reported accurately; and/or preregister their therapy trials, specifying in advance their methods and hypotheses, which makes the research process transparent and helps prevent the burying of negative findings.

Ethical therapists can continue to engage in practice that is evidence-based, not eminence-based, rooting their therapies in scientific evidence rather than their own conjecture or that of senior colleagues. They can also continue the routine outcome measurement many already employ: solicit therapy clients’ feedback early and often, be open to surprise about what’s working and what’s not, and adjust accordingly. Clients can ask their therapists upfront if they will offer the opportunity for such mutual assessment of their progress.

Therapy helps the vast majority of those who receive it. Happily – if the discipline embraces reform in research, and cultivates a humble, flexible approach to therapy – it could help even more.