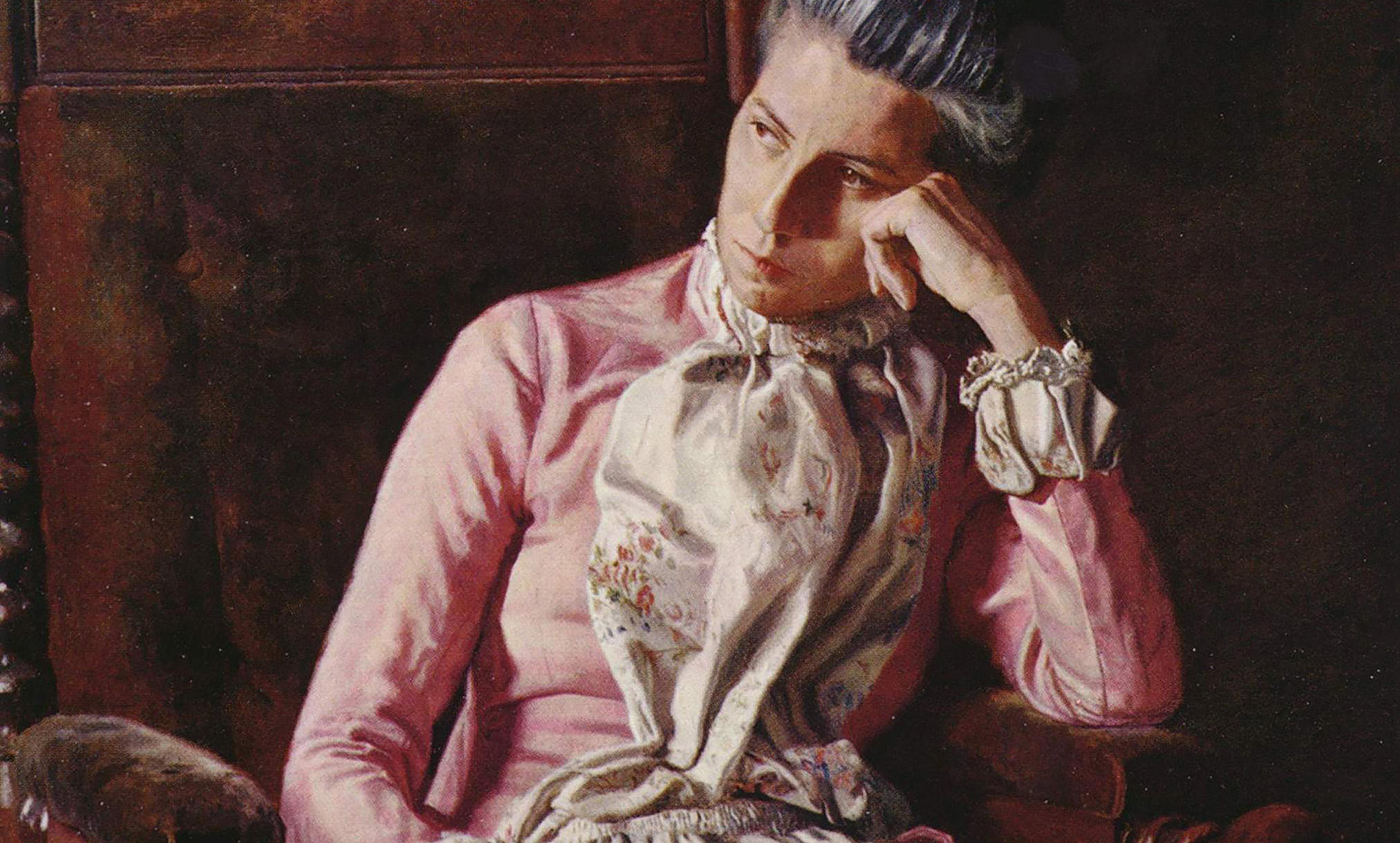

Miss Amelia Van Buren (circa 1891), portrait by Thomas Eakins. Courtesy of The Phillips Collection, Washington DC/Wikipedia

A previously unknown species – single people – has recently been discovered. First, there was Eric Klinenberg’s book Going Solo: The Extraordinary Rise and Surprising Appeal of Living Alone (2012), followed by Kate Bolick’s Spinster: Making a Life of One’s Own (2015) around the time that The Washington Post started a column about the single life called ‘Solo-ish’. Then came Rebecca Traister’s All the Single Ladies: Unmarried Women and the Rise of an Independent Nation (2016). ‘Single people are getting harder and harder to ignore,’ wrote Jesse Singal in New York magazine last year. In fact, single women were predicted to be the most powerful voter demographic in the recent presidential election in the United States. (There doesn’t seem to be the same attention paid to single men.)

It seems, then, that single people have finally arrived, poised to take their rightful place alongside married couples when it comes to status, power and respect. Except for one thing: single people still don’t have access to the legal benefits and protections the government grants to those who get married. In the US, there are more than 1,100 laws benefiting married couples, and that’s just at the federal level; many states offer perks and protections as well.

Spouses in the US can pass on Medicare, as well as Social Security, disability, veterans and military benefits. They can get health insurance through a spouse’s employer; receive discounted rates for homeowners’, auto and other types of insurance; make medical decisions for each other as well as funeral arrangements; and take family leave to care for an ill spouse, or bereavement leave if a spouse dies.

These privileges are unavailable to the unmarried in the US, yet most single people would benefit if they were. After all, singles are rarely all alone. They have parents, siblings and other relatives, they have close friends and, often, lovers. Why should they be denied the right to pass on their Social Security benefits to them when they die, instead of having their money absorbed back into the system? Why should they be denied paid time off work to care for them?

Considering that there are more than 124 million single Americans, by choice or chance – outnumbering those who have tied the knot – it no longer makes sense to have the government reward people for their romantic decisions. And, as Klinenberg notes, it’s not just a phenomenon in the US. The rise of people who identify as single is occurring across the globe, from India to China to Brazil to Scandinavia. In Stockholm, more than 50 per cent of all homes are one-person households – ‘a shocking statistic’ according to Klinenberg, but a statistic he predicts is here to stay, despite the long history of seeing single people as ‘lesser’.

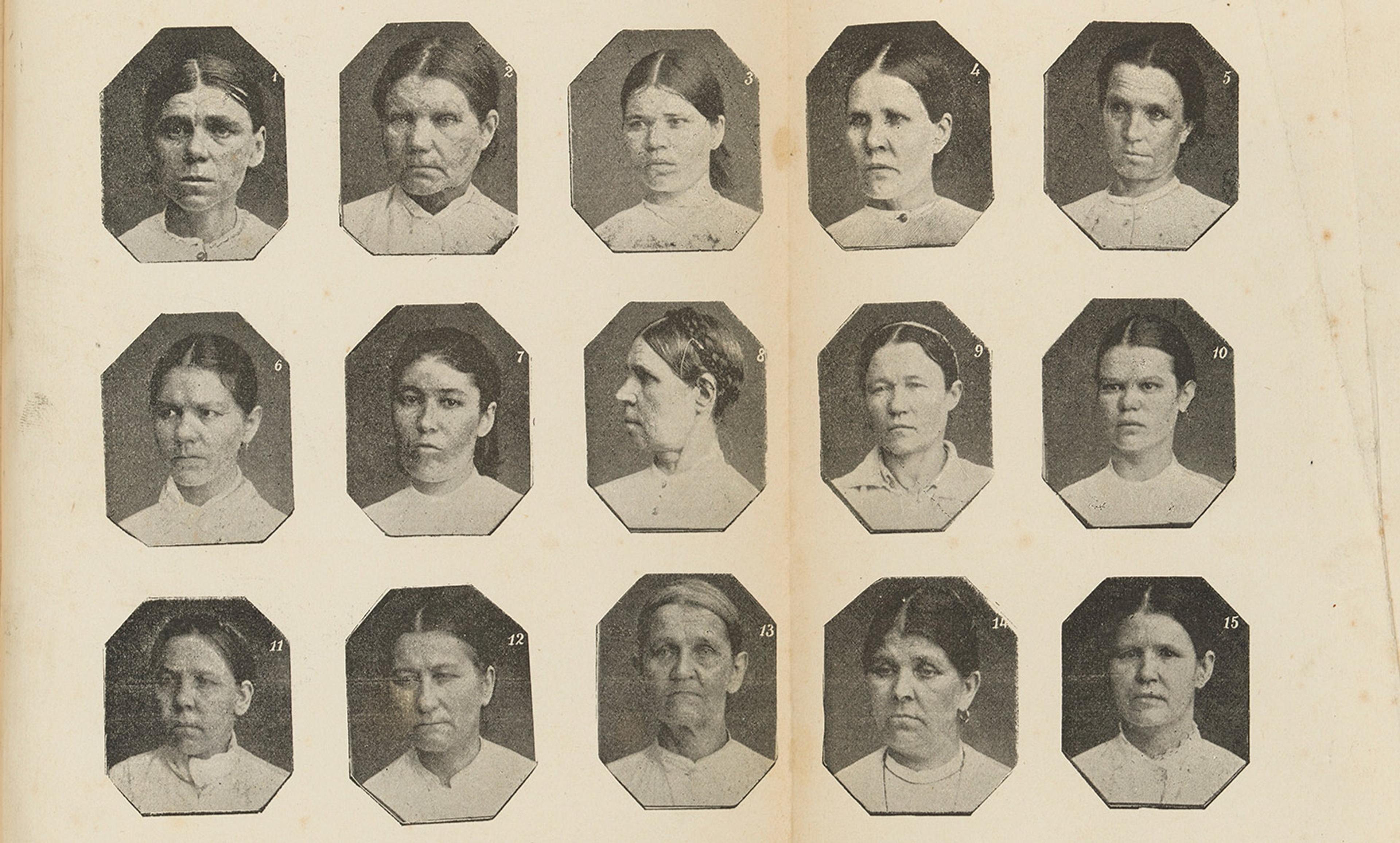

Historically, men who didn’t marry were considered immature playboys; women who remained single were sad, lonely spinsters. In both cases, their sexuality was suspect. Even today, when people have more freedom than ever to shape their lives, singles, especially women, are scrutinised, as any single person who has stayed with family for the holidays only to be barraged with questions about his or her love life knows all too well.

The idea that everyone aspires to a romantic relationship – or should – is what the philosopher Elizabeth Brake in her book Minimizing Marriage (2012) calls amatonormativity, and it’s harmful to those on a different path. Having the government shut them out of certain protections is punishing. This is similar to what “Singled Out” (2007) author and singles advocate Bella DePaulo calls ‘singlism’ – the policy of making singles pay more than couples for their basic needs.

Part of the problem is that there is no one type of single person. Singles include the never-married, the divorced and the widowed; the young and the old; hetero and LGBT; rich and poor; black, white and Asian, and every other possibility of race, ethnicity, gender, age and sexual orientation. Plus, many see the single life as a transitory phase, assuming that singles want to marry at some point. Some do, but others don’t. The bigger question is: why should it matter?

Granting benefits to married people made sense at one point, says the historian Stephanie Coontz, author of Marriage, a History (2005). In the mid-20th century, she writes, governments looked to marriage licences as a way to distribute resources to dependents, enacting the Social Security Act of 1935 to give married couples more benefits and the right to pass them on to spouses.

‘Every country, every nation, every state has found it useful to give certain benefits and protections to married people,’ Coontz tells me from her Washington state home. To entice someone to give up earnings to take care of the home and children, she – and it has overwhelmingly been women – would need to be protected. There were incentives to get married as well as obligations.

After the Second World War, there were numerous incentives that encouraged people to embrace male breadwinning and female homemaking, and in 1948 the US income tax code was changed to favour that model. Of course, in those days it was expected that everyone would marry – and would want to marry – and that women would remain at home. But that isn’t quite the reality any more, even though 69 per cent of millennials (people born between 1982 and 2000) say that they’d like to marry one day.

Today, the male breadwinner and female homemaker model is hardly the norm; 46 per cent of US families include parents who both work full-time. In Canada, it’s 69 per cent and in Australia it’s 58 per cent. This makes it harder to defend using marriage licences as a way to funnel benefits to people. Isn’t it time to give singles the same perks and protections to which married couples are privy?

For Coontz, it’s a no-brainer: ‘It’s absolutely overdue.’ Keeping the system as it is might appease the moralists among us, she noted in 2007 in an opinion piece for The New York Times, but it ‘doesn’t serve the public interest of helping individuals meet their care-giving commitments’. Even if men and women don’t have children of their own – and many married couples nowadays choose to be childfree – almost everyone has someone who will likely need to be looked after at some point, from a parent to a close friend. The law professor Martha Albertson Fineman argues in her book The Autonomy Myth (2004) that the government should stop privileging married couples, and offer the same perks and protections to anyone in a caregiving role. The law professor Vivian E Hamilton makes a similar argument in her paper ‘Mistaking Marriage for Social Policy’ (2004).

Earlier this year, women’s marches took place all across the globe. While these millions of men, women and children marched for different reasons, the overwhelming message was that women’s rights are basic human rights.

Can the same be said of single people’s rights? Of course. So will there be a unified, orchestrated effort to strip the benefits and protections that apply just to the married and give them to every individual, married or not?

‘I’m not optimistic,’ DePaulo says. ‘Advocacy groups never seem to get any traction or any significant funding. One issue is that marital status, unlike race or gender or sexual orientation, is changeable.’ And changing entrenched programmes such as Social Security is likely to face huge resistance from those who wish to maintain ‘traditional’ values.

Yes, creating a movement around one’s single status would be challenging. But reframing the conversation to become one that addresses basic human rights is much more unifying – and doable.