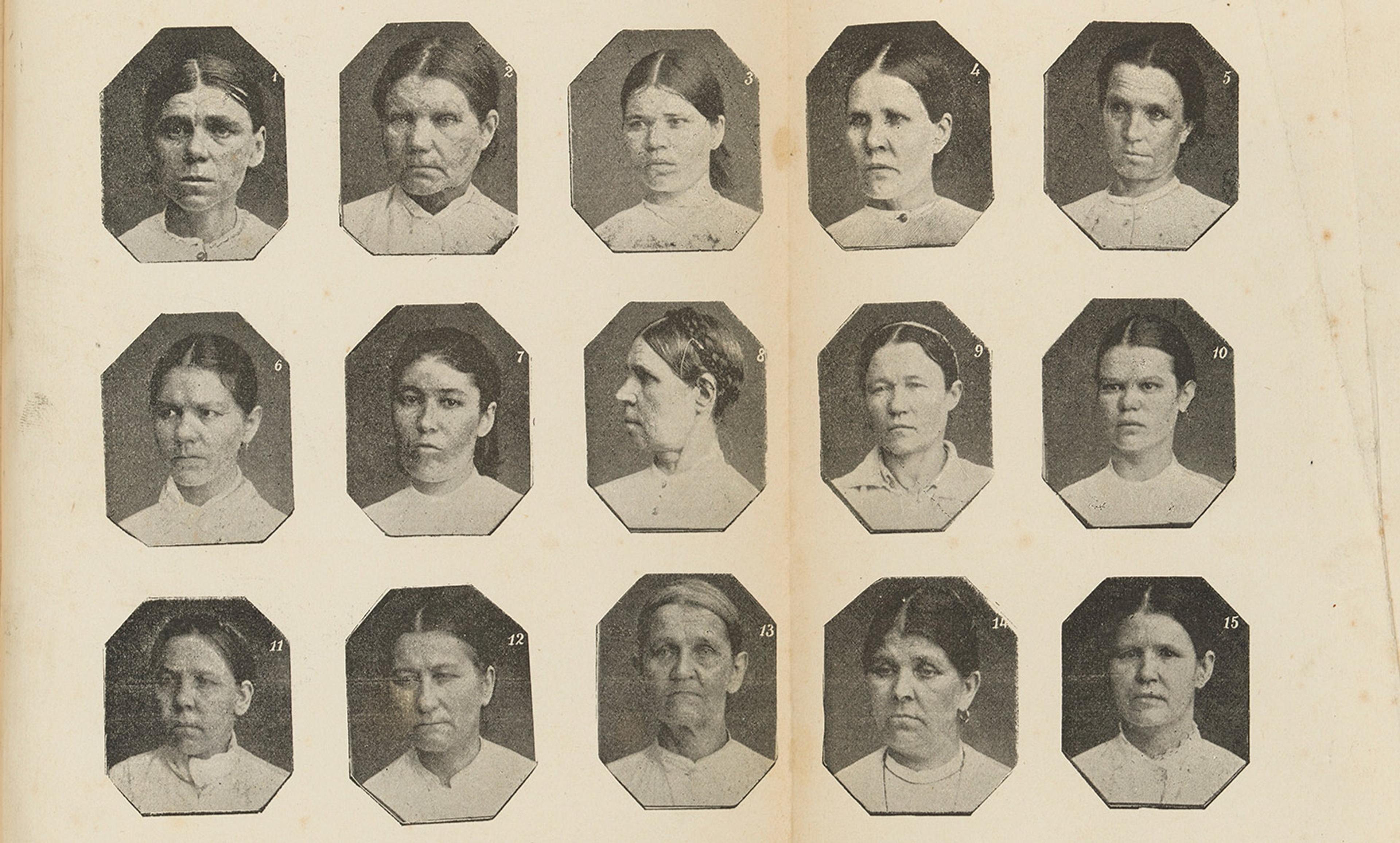

Jewish people forced to dig their own graves in Ukraine, 1941. Photo courtesy the German State Archives/Bundesarchiv

It was noon in early 1942 as Johann Grüner approached the ‘German House’ in the Polish town of Nowy Targ for lunch. As a mid-level Nazi bureaucrat in occupied Poland, he enjoyed the privileges of power and the opportunity for career advancement that came with duty in the East. The German House, a mix of cultural centre, restaurant and pub, was one of the privileges enjoyed by the occupiers. As he entered the building, he could hear a boisterous celebration within. At the front door, a clearly inebriated Gestapo official passed by, a beer coaster with the number 1,000 written in red pinned to his blouse. Addressing Grüner, the policeman drunkenly bragged: ‘Man, today I am celebrating my 1,000th execution!’

At first glance, the incident at the German House might appear to be a grotesque aberration involving a single depraved Nazi killer. However, such ‘celebrations’ were widespread in the occupied Eastern territories as members of the notorious Schutzstaffel (SS) and the German police routinely engaged in celebratory rituals after mass killings. In fact, among the perpetrators of genocide, heavy drinking was common at the killing sites, in pubs and on bases throughout Poland and the Soviet Union. In another horrific example, a group of policemen charged with the cremation of some 800 Jewish corpses used the occasion to tap a keg. In this case, one of the men, named Müller, had the ‘honour’ of setting fire to ‘his Jews’ as he and his colleagues sat around the fire drinking beer. In a similar case, a Jewish woman recalled the aftermath of a killing operation at Przemyśl in Poland: ‘I smelled the odour of burning bodies and saw a group of Gestapo men who sat by the fire, singing and drinking.’ For these Gestapo men, ‘victory celebrations’ proved to be the order of the day, and followed every killing action or ‘liberation from the Jews’.

The role of alcohol in the Nazi genocide of European Jews deserves greater attention. While numerous studies from the social sciences have demonstrated the link between drinking and acts of homicide and sexual violence, the connection between mass murder and alcohol is under-researched. Among the Nazi perpetrators, alcohol served several roles: it incentivised and rewarded murder, promoted disinhibition to facilitate killing, and acted as a coping mechanism. In the field of Holocaust Studies, explanations of perpetrator motivation embrace a variety of instrumental and affective factors ranging from ‘ordinary men’ guided by peer pressure, obedience to authority and personal ambition, to ‘willing executioners’ imbued with anti-Semitism and racial hatred; however, alcohol consumption facilitated acts of murder and atrocity whether by ordinary men or true believers.

In the early 2000s, Father Patrick Desbois used ‘ballistic research’ to find spent firearm cartridges in order to chart where SS and police death squads had massacred entire Jewish communities in Ukraine. Contrary to popular belief, he found that many of these killing sites were ‘in the middle of towns, in full view and with the knowledge of everyone’. Not only were these massacres conducted in public spaces, but non-Jewish Ukrainian witnesses often remembered the killers’ use of alcohol.

As a girl, Hanna Senikova observed a mass execution by the SS and policemen in her hometown of Romanivka. After the arrival of the Germans, her aunt had been forced to cook for the perpetrators who ordered a banquet in advance of the massacre. Interviewed by Desbois in his book The Holocaust by Bullets (2008), Senikova recalled:

They wanted to eat nothing but large pieces of meat … Then some of them shot the Jews while others ate and drank. Then, those who had eaten went to shoot the Jews again while those who had been shooting them before came to eat … They were drinking, singing. They were drunk. They were shooting at the same time. One could see little arms and legs coming out of the edge of the pit.

In a similar example, Wilhelm Westerheide, a Nazi regional commissar in Ukraine, participated in a two-week massacre of an estimated 15,000 Jews. During the shootings, Westerheide and his accomplices ‘caroused at a banquet table with a few German women … drinking, and eating amid the bloodshed’, while music played in the background during a surreal killing party described by Wendy Lower in Hitler’s Furies (2013). In this case, the perpetrators’ use of alcohol provided a means for establishing camaraderie and lowering inhibitions as they proceeded with their gruesome task.

While death squads celebrated among their victims’ graves in the field, local bars and restaurants also served as sites for celebrating acts of mass murder, where heavy drinking was often accompanied by songs that emphasised Nazi masculine ideals of hardness, camaraderie and violence. In a bar in the Polish town of Wejherowo, one witness overheard a group of SS men ‘who had obviously just come from a shooting’ discussing how ‘The damned brains [of the victims] just squirted everywhere.’ Similarly, Marianna Kazmierczak, then a 17-year-old Polish girl working at a restaurant in Zakrzewo, testified that SS men routinely gathered there to drink beer and schnapps, and to celebrate after mass killings in the fall of 1939. In testimony quoted in War, Pacification, and Mass Murder, 1939 (2014) by Jürgen Matthäus, Jochen Böhler and Klaus-Michael Mallmann, she remarked:

Finally, they were half-drunk, and the mood was very merry, as if they were intoxicated. They sang and danced … Such drinking bouts were repeated after every mass shooting … sometimes several times a week. The drinking bouts went on into the late hours.

Ultimately, singing and drinking were ritual acts of celebration, and served as mechanisms for promoting male bonding and identification with the group and its genocidal charter. In such cases, alcohol was in parts a reward for murder, a lubricant for male bonding, and a means for coping.

After their transfer to Warsaw in January 1942, members of Police Battalion 61 established a bar outside the Jewish ghetto. The ‘Krochmalna’ bar not only provided a place for off-duty policemen to engage in ‘drinking orgies’, but also as a site of celebration and male competition with respect to murder. Individual policemen competed for number of Jews killed and bragged about their ‘scores’. These policemen were not alone as the men from other units also kept track of their kills. A former policeman with Police Battalion 9 testified after the war: ‘I also know that several [men] kept exact count of the number of people they had shot. They also bragged amongst themselves about the numbers.’ In the case of Police Battalion 61, the bar’s front door served as the unit’s tally board, with an estimated 500 notches arrayed in groups of five, designating the number of Jews murdered by its patrons. During a postwar investigation of the unit’s activities in Warsaw, one state prosecutor commented that ‘victory celebrations’ were a customary part of the unit’s ritual after mass executions.

The linkage between alcohol, atrocity and celebratory ritual was not unique to the Eastern Front. During the Rwandan genocide, the French journalist Jean Hatzfeld interviewed Hutu perpetrators, and noted in his book Machete Season (2003) the importance of local cabarets (bars) as social gathering sites and places for planning, organising and celebrating violence against the moderate Hutu and Tutsi victims. One Hutu perpetrator observed:

[The killers] went around together. You saw that they shared and shared alike with field work and drink at the cabaret. During the genocide I know that gang went out cutting from the first day to the last.

Another female witness described the distribution of the plundered possessions of the victims and the nightly celebrations: ‘The men sang, everyone drank, the women changed dresses three times in an evening. It was noisier than weddings, it was drunken revelling every day.’ At least for these men and some women, the killing field and the bar became sites for group socialisation and celebration in the wake of mass murder.

While intoxication was not a prerequisite for genocide, it is clear that alcohol and drinking rituals were an important element in the celebration of genocidal massacre in the Nazi East – whether taken in shots from a table laden with smoked sausage and vodka, swilled from a bottle at the edge of a ditch, or consumed in post-execution beer parties. The SS man celebrating his 1,000th killing was not only intoxicated at his party, but in a real sense drunk with the act of murder itself.