My younger brother and I called him ‘the old lizard’ (on account of his reptilian resemblance — and to irk our mother, his partner at the time). To his enemies, he was a crackpot, fraud, and a cheat. And to his patients, and many of his friends, he was a source of support, an open listener, a sage and protector.

Dr John E Mack was many things to many people. A Harvard-trained psychiatrist, tenured professor, and one of the founders of the Cambridge Hospital Department of Psychiatry (a teaching hospital affiliated with Harvard University), John held an impressive command and was respected in his field. After an early career spent working on issues of child development and identity formation, he won the Pulitzer Prize in 1977 for his psychoanalytic biography of Lawrence of Arabia, entitled A Prince of Our Disorder (1976). Then, in the late 1980s, John put his reputation on the line when he started investigating the phenomenon of alien abduction.

It all started innocently enough. He began holding sessions with patients or ‘experiencers’ (as they’re called) who believed they’d been abducted. He ran hypnotic regressions from our home, and he gradually came to furnish enough evidence for a book, Abduction: Human Encounters with Aliens (1994). This was followed in 1999 by Passport to the Cosmos: Human Transformation and Alien Encounters. His standard line with the outside world was (as given to the BBC): ‘I would never say, yes, there are aliens taking people. [But] I would say there is a compelling powerful phenomenon here that I can’t account for in any other way, that’s mysterious… I can’t know what it is but it seems to me that it invites a deeper, further inquiry.’

In the privacy of our home, where he was a regular presence, John was bolder in his claims. Aliens were real — it was just that their existence threatened the dominant logic of our worldview. John attributed society’s failure to account for the abduction experience as a cultural failing. Alien abductees weren’t deranged or mentally ill — we just didn’t have a way of interpreting and understanding what they’d been through. Rather than label these peoples’ experiences as a new disorder or syndrome, John argued that we had to probe into and change our perception of reality to account for this phenomena. The subtext: we had to allow for the existence of aliens.

For more than a decade, from the time I was eight until I was of legal age, I was witness to these debates and to the politics surrounding John’s ‘coming out’ in support of abduction phenomena. My mother, an anthropologist by training, was John’s primary research assistant. They bought a house together in Cambridge, Massachusetts and my brother and I visited them once a month and during school holidays. The rest of the time we lived with my father and stepmother in Arlington, Virginia.

Like many of his colleagues, I viewed John with a mixture of scepticism and intrigue. Part of my scepticism can be put down to the fact that he was dating my mom; but a good fraction of it owed to my sense of reality being overturned by the postulation of ‘greys’ — a particular manifestation of extraterrestrials, known for their large heads, huge almond eyes, and shortened, pretty much featureless bodies.

At eight, and still learning to distinguish between fantasy and reality, the imposition of adults who believed in aliens was confusing and anxiety-provoking, but adventurous and thrilling too. I was fairly sure that Santa Claus wasn’t real. But I wouldn’t have bet my life on it. My stuffed animals and toys had only just lost that animistic quality — becoming mere playthings, instruments of the imagination, as opposed to real creatures with essences all their own. As for aliens, I couldn’t be sure. Flying on airplanes between my parents’ houses I’d sometimes be on the lookout for a hovering metallic orb.

It was 1992 when John entered our lives. Bill Clinton was president, and Kurt Cobain dominated the airwaves. It was the end of the Cold War stand-off, and the political scientist Francis Fukuyama had just published his book The End of History and the Last Man, where he wishfully predicted that human evolution had come to an end with the triumph of Western liberal democracy. Everything was smooth sailing. We no longer had the threat of communists, but we didn’t yet have the threat of terrorists. In need of a symbolic enemy, aliens personified an important ‘other’ — a dystopian warning to our Western culture’s all too eager triumphalism.

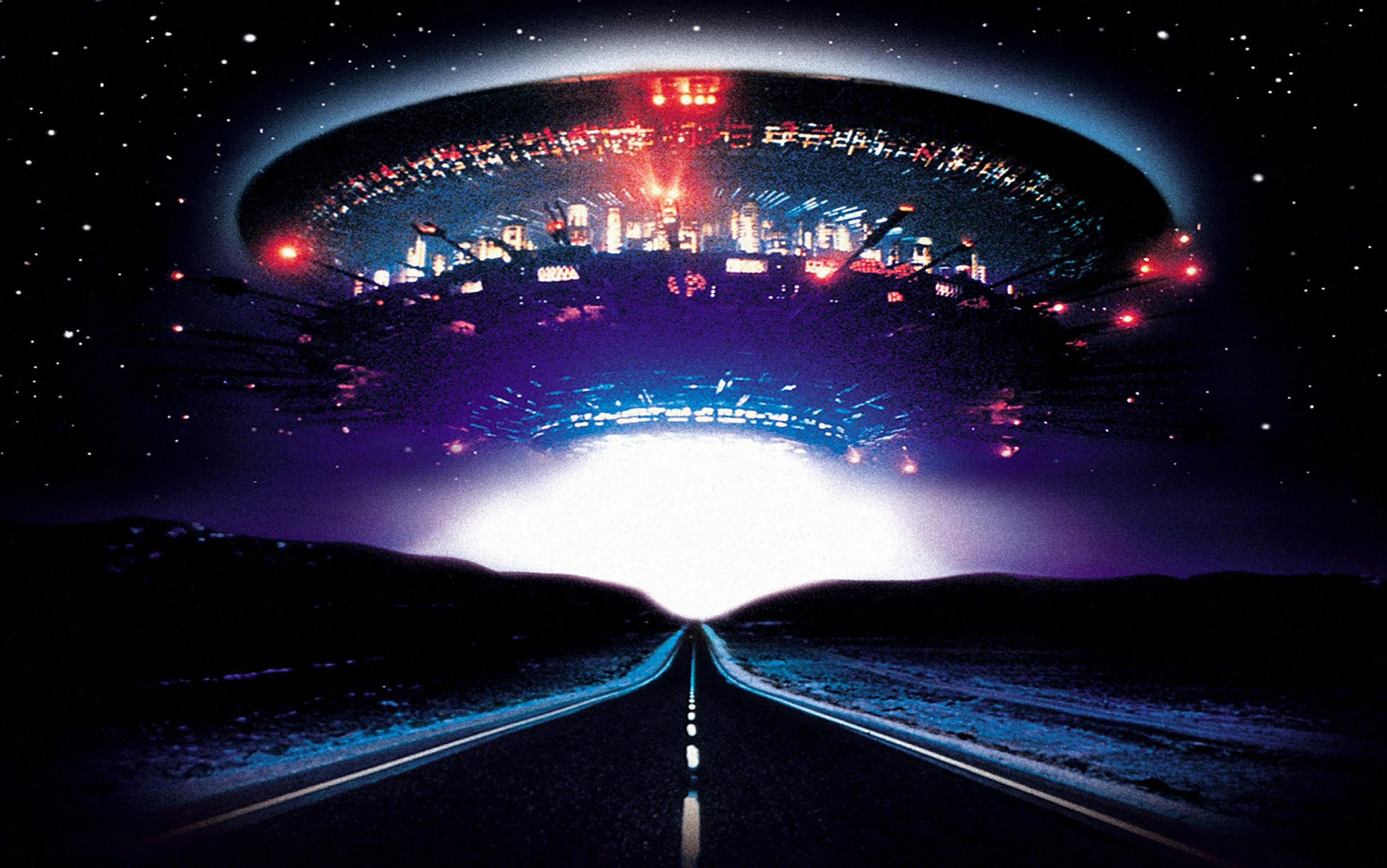

On television, the paranormal soon paraded around on shows such as Roswell and The X-Files, which explored extraterrestrial phenomena in the shadow of government cover-ups and conspiracy. Flip channels and you might have caught Arthur C Clarke’s equally other-worldly 26-part series Mysterious Universe . It’s no wonder that the 1990s saw a rush of alien appearances in the popular imagination. The impending millennium brought with it the arrival of a future that had always been distant. As the political scientist Jodi Dean, author of Aliens in America (1998), articulated at the time, the appearance of aliens corresponds to our ‘anxieties over technological development and our growing consciousness of ourselves as a planet and our fears for the future at the millennium’.

There is some truth here. When I asked my mom and John growing up what the aliens intended (subtext: ‘Do they come in peace or should I be really scared?’), they said that many experiencers felt that aliens communicated an environmental message about the urgency of saving the planet.

At the same time, many of the abductees that John interviewed attested to the technological superiority of the alien race. I was told stories about patients who experienced aliens that could pass through walls, were able to communicate with extrasensory perception (ESP) and mind-reading, and perform medical experiments on humans without invasive surgery. In this light, aliens provided an outlet for all our fears of technological domination. To have an experience of aliens was to realise that the human race might not represent the pinnacle of evolution, that we were perhaps inferior to extraterrestrial life.

In daylight, I was sceptical (the good little rationalist), but night-time brought with it a tide of magical thinking

But as a kid largely ignorant of grander sociological forces, aliens were only one thing: scary. They had large black eyes and androgynous forms. And they were real — like ghosts and witches and monsters. In daylight, I was sceptical (the good little rationalist), but night-time brought with it a tide of magical thinking. I used to lie in bed and worry that maybe I would be abducted. I would even make supplicating promises of better behaviour in the hope of bartering with these outsiders — ‘I’ll be good, just leave me alone.’ In my secular progressive household, aliens offered a moral disciplining authority, an invisible spectator to police my actions.

After many years elapsed without any sign of extraterrestrial visitation, I began to feel ignored. My fears turned to pangs of dejection: ‘Wasn’t I special?’ ‘Shouldn’t I be a chosen ambassador for the human race?’ Or even: ‘If the aliens were really out to create a master race (as I overheard), didn’t they want my DNA?’

John had many of the same laments. They weren’t the ego bruises of a child in pursuit of some fantastical ambassadorial calling, but they were in the same genre. He felt passed over. He longed for an encounter. He was the public face of this movement and yet he had only secondary experience of the abduction phenomena. Having spent more than 15 years listening to other people’s encounters with these mythical beings, he wanted some evidence beyond the testimonials he gathered from his patients. He wanted to be visited. We all did.

Just as important, a visitation would have answered the growing chorus of critics lining up on the ‘respectable’ side of John’s working life. Many of his colleagues thought he’d gone crazy. He, in turn, felt betrayed by those academic collaborators who failed to support his work. John’s biggest critics called into question his use of hypnosis. In keeping with Freud’s theory of ‘repression’ — which held that the mind can banish traumatic memories to prevent us from experiencing anxiety — much of John’s research invoked the idea of recovered memory, whereby, through hypnosis, you could get a patient to go back into repressed traumas and recall their abduction experiences.

I remember one summer evening in a beach house on Martha’s Vineyard when I was about 11, we all watched as John regressed my aunt back into a past life. She lay on the couch recalling an incident in which she was a forest ranger who witnessed the death of a few people during some kind of avalanche. My aunt later told me that she was fully conscious of the experience, but couldn’t control what she was saying. It was like she was watching herself tell a story. John later tried to hypnotise my brother so that he wouldn’t be afraid of spiders.

Ultimately, the question that plagued memory excavators like John was whether these repressed memories, divulged under hypnosis, were mere ‘artefacts’ of the mind, or else legitimately true recollections. John’s tendency towards a more literal interpretation of his patients’ experiences with aliens was controversial.

John described the investigation as ‘Kafkaesque’. He never quite knew the status of it or the nature of the committee’s complaints

In 1994, the dean of Harvard Medical School called a committee of peers to investigate John’s scholarship. This was the first time a tenured professor had ever been subject to an investigation. It was, effectively, an inquisition that some likened to a ‘witch hunt’, and it left John feeling persecuted and misunderstood. John described the investigation as ‘Kafkaesque’. He never quite knew the status of it or the nature of the committee’s complaints. Unable to accuse John of any ethical violation or professional misconduct, its aim was to ask, as Harvard law professor Alan Dershowitz put it, ‘whether a Harvard Medical School professor ought to be lending his credibility to stories of space alien abductions’. To Dershowitz, this was a dubious goal. ‘No great university should be in the business of investigating the ideas of its faculty,’ he wrote in the university magazine, in 1995. In the end, the dean reaffirmed John’s academic freedom to study what he wished and to state his opinions without impediment. But the damage had already been done.

As his professional credibility faltered, John’s anxiety and anger began to rise. John cared about his reputation. It was not easy to become persona non grata in the very institutions he had helped to build. He was used to working within established professional systems, and when those very institutions called his integrity into question, he sought out allies in other like-minded people. He grew an entourage of support among shamans, experiencers, and celebrities.

Our household became a living altar to an esoteric band of misfits who were regular houseguests and interlopers. One morning, when I went to get some orange juice from the kitchen, the actor Woody Harrelson was there, drinking coffee with John at the table. It was normal. Normal was also being offered a peace pipe by Sequoia, a Native American shaman who blew tobacco in our youthful faces and challenged us to seek out greater visionary experience.

By 13, however, I was ready to move on. John and my mother were headed to the Australian outback for a year to speak with Aboriginal people about their experiences with aliens. My brother and I were invited to go along: our formal education would be satisfied by distance learning packets, while our real education, as I understood it at the time, was to be some combination of didgeridoo and Aboriginal creation myths. But something inside me desired stability and order. I longed to be absorbed into an antiseptic American culture where lacrosse, school dances and flared blue jeans were ends in themselves; where ordinary reality wasn’t usurped by the fantastical.

My brother and I ultimately opted to stay behind. We stayed living with my father and stepmother, and succumbed to a deliciously comfortable white picket-fence existence (literally, the fence was painted white). We became absorbed in teenage politics and concerns. And the only flying saucers we encountered were Frisbees.

Later on, at college at Brown University, I gave myself licence once again to explore the magical thoughts of my youth, not least the idea that reality was merely a construction. As an adult, it was a less threatening prospect. Rather than induce existential panic, it furnished reputational accolades. I ended up writing a thesis about 17th-century astrology and the fashioning of scientific boundaries. It was an ode to John in some ways. I wanted to understand how ‘science’ became ‘science’. Many of the astrologers of the time were booted out of the emerging scientific establishment — some were even put on trial for instigating civil disorder. It was not unlike John’s own experience, when his psychiatric methods were called into question by the scientific establishment.

Before my thesis was published, John was hit by a drunk driver and killed, in London. It was 2004. Immediately after his death, my mother began receiving phone calls from clairvoyants who claimed to have communicated with John, ‘on the other side’. Before he died, John had begun outlining a manuscript on the power of love, based on the stories of those who had been able to communicate with loved ones after death. It was a surreal experience for my mother to be experiencing such intense grief, while at the same time receiving phone calls from people who had reportedly been in conversation with John after the accident.

After John died, aliens seemed to vanish from household discussion almost entirely. It felt like the public’s interest had also waned. When I asked my mother why the phenomenon had seemed to die down, I was told that the aliens were placing less emphasis on the Western world; that they were more interested in China. And that’s where we left it.

But if I reflect on the impact of my childhood experience, I think it left me with a profound openness, and a generous ear. John taught me the power of listening; really hearing people out and having the courage and resilience to question established orthodoxies. I still remain entirely agnostic about the existence of aliens. I have a commitment to preserving unknowns, and I thrive on ambiguity and complexity in my work and my relationships. John’s legacy has also left me with a certain reverence for misfits, for outliers and challengers of the status quo: for the type of person who walks the line between delusion and insight.

John, too, remains immortalised in my mind as someone with great courage and empathy. I associate him with a period of my childhood wrought with big questions. Bearing witness to the craziness that surrounded those ten years of cosmological exploration left me with a shaky groundwork in which reality was never quite what it seemed, but it also furnished me with a profound sense of awe and wonder about the world.

I feel incredibly grateful for the experience. To be exposed at such a young age to a zeitgeisty obsession with deprogramming, where Western culture was perceived as an enemy of consciousness and truth, was an education that left me with a residual feeling of always being on the outside of mainstream culture. There is a part of me that also looks back with nostalgia for a time when the primary conversation was a probing of the cosmological – when we weren’t all busy on our laptops, stressed about finances, or waiting with bated breath for the next season of Homeland; but were concerned, rather, with ancient and meta-questions about our role in the universe and the existence of life elsewhere.