In July 2019, I visited Siang Sawn, a small village in Chin State, western Myanmar. Sparsely populated, mountainous and underdeveloped, Chin State is one of the least accessible regions in Myanmar. In the monsoon, roads across Chin State – mostly dirt lanes – turn into pools of sludgy mud, extremely toiling to traverse. Stunning mountains shrouded in clouds dominate the horizon.

On a rain-soaked monsoon afternoon, I was in Siang Sawn to learn about Laipianism, a local religion practised in Chin State. It is one of the last surviving, well-organised Indigenous faiths that emerged in the early 20th century as a response to the spread of Christianity in colonial Southeast Asia. Siang Sawn is considered the ‘spiritual homeland’ of Laipianism, a religion that has only about 5,000 followers. In the overwhelmingly Christian Chin State, this remote village is an exclusive home to its followers. With a population of a little under half a million, the Chin people (also called Zo) are considered a taingyinthar – ‘Indigenous’ race – in Myanmar. At least 90 per cent of the Chin adhere to one or another denomination of Christianity. The rest follow Theravada Buddhism, Burmese nat cults, and Laipianism. Home to 300 people, Siang Sawn is a self-sufficient pastoral community of farmers who cultivate paddy, keep kitchen gardens and rear animals.

Walking past a few evenly spaced, bungalow-like brick houses through the main street in Siang Sawn, I came upon distinctive Laipian religious architecture: a dome-shaped mirrored building that housed an effigy and heavenly portraits of a revered man, Pau Cin Hau. The building is a place of worship, and Pau Cin Hau’s portraits also adorned the doors of each house.

A Laipian hall of worship in Myanmar. Courtesy Kam Suan Mang

A Chin healer and dreamworker, Pau Cin Hau (1859-1948) was the founder of Laipianism. The religion is believed to have originated with a series of dreams he had in 1900, in which he would see an elderly man with a radiant halo around his face. In one of the first dreams, the iridescent, saintly figure hands Pau Cin Hau a book containing certain symbols and teaches him to make certain shapes. Then, over a period of two years, he sees various symbols come afloat in recurring dreams. With these symbols, in 1902 Pau Cin Hau came up with a logographic script for the local Chin language – the first time the spoken language was rendered in writing, and a watershed moment in Chin history. Later, he simplified the script into an alphabet consisting of 57 characters. The script came to be known as lai, which means ‘reading and writing’, ‘script’ and ‘literature’ in the Chin language. The invention of the script earned Pau Cin Hau the moniker Laipianpa, meaning ‘the script creator’.

Pau Cin Hau, in longyi and donning a turban, (second from right) in an undated photo with colonial officials and Christian missionaries. Courtesy Kam Suan Mang

Pau Cin Hau said that the haloed figure he’d been seeing in his dreams was Pathian (also spelled Pasian), ‘the creator of heaven and earth, the healer of all diseases.’ And that Pathian had instructed him ‘to spread the message that the Chin people should worship only Pathian, not any other spirit.’ Soon, Pau Cin Hau started preaching monotheistic teachings to worship one God, Pathian. Locals would come to call Pau Cin Hau’s teachings Laipian Pawlpi, ‘the religion of the script creator’.

In traditional Chin cosmology, people believed in a number of spirits of nature collectively called dawi, like the nat spirits of the Burmese. The greatest of these dawi spirits was Khuazing. However, the Chin also had a somewhat vague concept of an all-powerful higher god whom they called Pathian. A British military administrator in the region, Thomas Herbert Lewin, popularly known among the Chin as Thangliana, recorded a Chin man’s religious beliefs in his book, Wild Races of South-eastern India (1870). The Chin man told Lewin that they believed in two gods: Patyen (Pathian) and Khozing (Khuazing). Pathian ‘is the greatest: it was he who made the world’. The other god, Khuazing, ‘is the patron of our tribe, and we are specially loved by him,’ the man insisted. ‘The tiger is Khozing’s house-dog, and he will not hurt us, because we are the children of his master.’

From this description, Khuazing seems to fit the definition of what the anthropologist Marshall Sahlins calls a ‘metaperson’, found in traditional cosmologies worldwide. In The New Science of the Enchanted Universe: An Anthropology of Most of Humanity (2022), Sahlins defines metapersons as ‘other-than-human persons endowed with greater-than-human powers’ who own beings, places and resources, and determine human fate in everyday life. Khuazing is thus a metaperson of Chin cosmology who owns the forest – hence the tiger is his house-dog. The Chin made offerings to Khuazing and his subordinate dawi spirits in spots near water sources, beneath trees, at hallowed rocks, in forests and at the entrance of villages. This was an ‘immanentist ontology’, a worldview defined by the attempt to call upon a supernatural power to assist life in the here and now – to ensure wellbeing, to make the fields fertile, and the sick healthy. This power was seen to be the gift of metapersons like Khuazing.

In 1902, Pau Cin Hau started preaching that the Chin should stop making sacrifices to Khuazing and other dawi spirits – the immanent metapersons or gods – and should instead pray solely to Pathian, the transcendent God. This new theology preached by Pau Cin Hau, albeit built on traditional Chin cosmology, was a form of transcendental revolution. In the book Zo People and Their Culture (1995), the historian Sing Khaw Khai states that: ‘It was Pau Cin Hau who proclaimed that the [Pathian] were only one God. He announced that [Pathian] was the supreme being who created the universe … [Pathian] stood for God and all other living divinities were collectively referred to as Dawi.’ Pau Cin Hau preached that, by paying obeisance to God (Pathian), any threat from the dawi spirits was averted. Thus, the Pau Cin Hau movement was indeed an example of a switch to transcendentalism.

By the 1930s everyone who was not a Christian was a follower of Pau Cin Hau’s religion

The move from immanentist practices towards transcendentalism is a global phenomenon in history. Sahlins argues that the ‘enchanted universe’ of immanentist religions largely gave way to transcendentalist religions that arose in much of the world in the Axial Age of the final centuries BCE. In Unearthly Powers: Religious and Political Change in World History (2019), the historian Alan Strathern shows that the switch to a transcendental religion is often a result of conquest and contact with monotheistic cultures. In the case of the Chin Hills – conquered by the British in the early 1890s – this shift may also have been triggered by colonial contact and conquest. Arthur and Laura Carson, the first Christian missionaries to the Chin people, landed in Haka, the capital of the Chin Hills, in 1899 – a year before Pau Cin Hau claimed to have had the first of many of his dreams about Pathian, his teachings and the script.

Chin society was initially reluctant to accept new religious ideas – both Christianity and Pau Cin Hau’s teachings. While the Carsons got the first convert after five years, in 1904, Pau Cin Hau started to attract the first of his followers only around 1906. ‘I stood alone in my faith for three years during which time the members of my own family, even, reviled instead of encouraging me,’ Pau Cin Hau told J J Bennison, the superintendent of census operations in Burma, recounting the early days of the movement. ‘But gradually, as my neighbours and even people from distant villages saw me still enjoying sound health, my religion began to spread, until after six years people from all parts of the hills became my fellow worshippers.’

In spite of its initial rejection, Pau Cin Hau’s religion effectively became, in just a few decades, the traditional Chin religion, outnumbering Christians at the time. In 1967, E Pendleton Banks, a Harvard-trained anthropologist who studied Laipianism, noted: ‘The usual reply of a non-Christian to the inquiry of a government official or a census taker about his religious affiliation was “Pau Cin Hau”.’ Thus, by the 1930s everyone who was not a Christian was a follower of Pau Cin Hau’s religion.

The first anthropologist to write on the Pau Cin Hau movement, H N C Stevenson, contended in his thesis, submitted to the University of London in 1943, that the primary appeal of Pau Cin Hau’s religion over Christianity rested on the fact that Pau Cin Hau allowed his followers to drink zu, the traditional alcoholic drink that the Christian missionaries sternly forbid.

While it began as an Indigenous reform movement, Pau Cin Hau’s movement would soon compete with Christian missionaries as proselytisation intensified in the Chin Hills. Somewhat paradoxically though, the Pau Cin Hau movement also laid the groundwork among the Chin for the spread of Christianity – the religion that the majority of Chin practise today. Two modern Zo scholars, the historian Pum Khan Pau and the theologian Philip Cope Suan Pau contend, in the former’s words, that ‘the early success of the Pau Cin Hau movement facilitated the growth of Christianity’. Once Chin society accepted Pathian as the supreme being following Pau Cin Hau’s teachings, it became easier for the missionaries to communicate the Christian gospel. Over time, ‘Pathian’ would become the name of the Christian God through a process of semantic reconfiguration of the term. Locals actively participated in the process of missionary translation through the Pau Cin Hau movement. Pau Cin Hau’s monotheistic teachings had already popularised the idea of one supreme being, Pathian, and made the community ready to accept the missionary translators’ semantic reconfiguration of the term to refer to the Christian God.

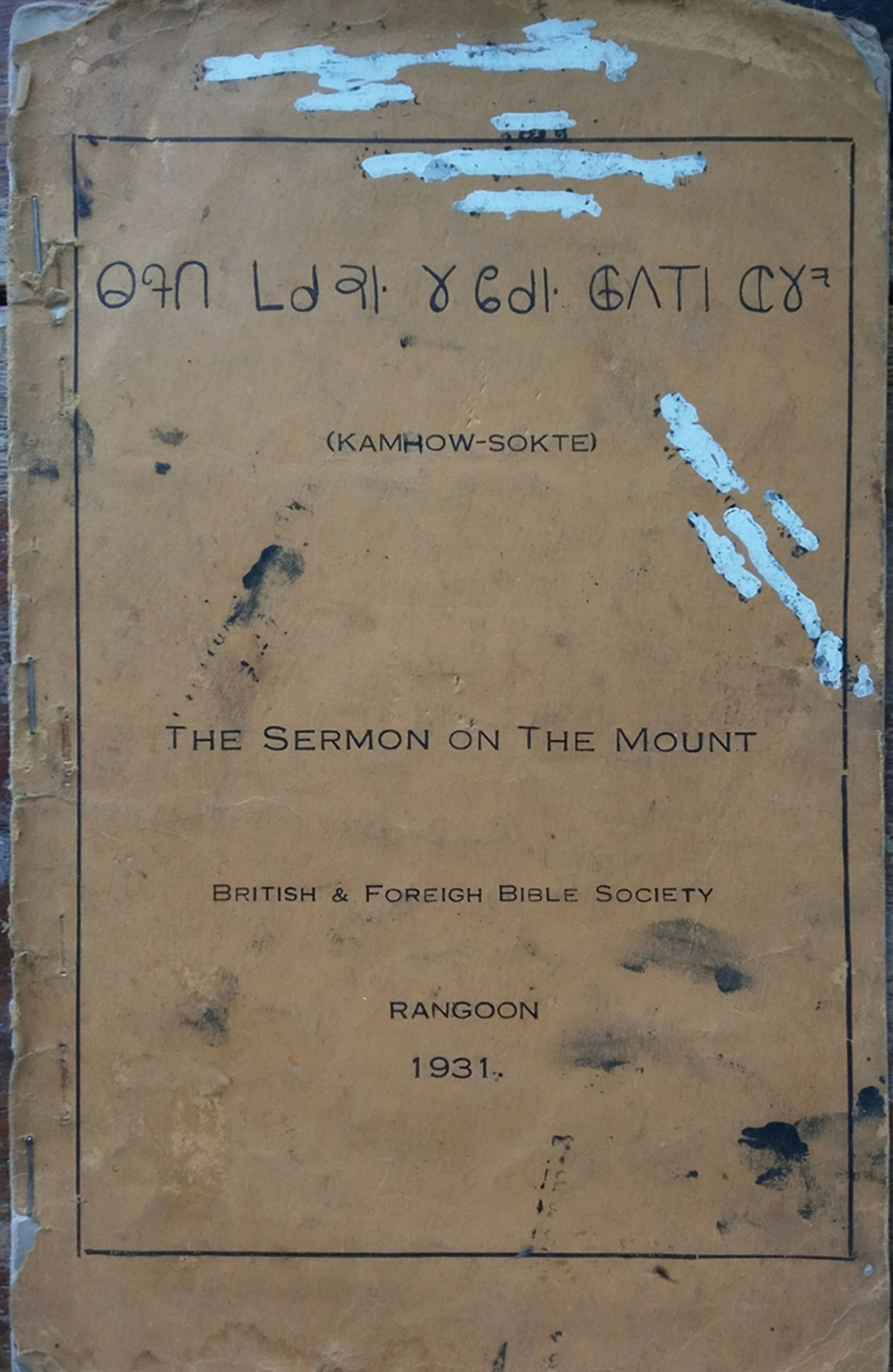

‘The Sermon on the Mount’ in Pau Cin Hau script. Photo Bikash K Bhattacharya

Christian missionaries themselves nonetheless held an ambivalent view of Pau Cin Hau’s religion. Some saw the shift to monotheism introduced by Pau Cin Hau as an awakening and a precursor to acceptance of Christianity, while others thought of it as an impediment to the spread of Christ’s gospel. The 33rd Annual Report of the British and Foreign Bible Society (Burma Agency) in 1932 stated that Pau Cin Hau’s ‘worship of one Creator God seems to be drawing near to genuine Christian ideals … with sympathetic and wise leadership this indigenous and spontaneous quest after higher things can be turned into a definite movement towards Christianity.’ On the other hand, Joseph Herbert Cope, a Baptist missionary stationed in the Chin Hills at the time, maintained that hundreds of Chin were ‘wasting their time’ on Pau Cin Hau’s script and his ideas.

There are certain structural similarities between Laipianism and Christianity

Some scholars consider Pau Cin Hau’s religion a version of local Christianity. In 1943, the anthropologist H N C Stevenson wrote that ‘the [Pau Cin Hau] cult was an indigenous variation of Christianity better suited to the local conditions.’ And in 2013, the historian Bianca Son Suantak wrote in her thesis at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London that Pau Cin Hau’s religion was a ‘carbon copy’ of Christianity.

Despite the views of these scholars, Elizabeth S Cope, who served as a missionary in the Chin Hills for 30 years and whose husband was the pioneer missionary Joseph Herbert Cope, stated that Pau Cin Hau was not a convert and indeed always opposed the missionaries. Thang Za Dal, a contemporary Chin intellectual and the author of The Chin/Zo of Bangladesh, Burma and India: An Introduction (2014), doesn’t agree that Pau Cin Hau’s religion is a version of Christianity. ‘There is really nothing about the Bible, Jesus Christ or the fullness of Christian ethical and moral teaching in Pau Cin Hau’s doctrine,’ he writes. ‘It has its own scriptures consisting of six books called Bu, all written in Pau Cin Hau script, that outlines its religious-spiritual system,’ Further, in an interview in 2020, Dal told me that researchers don’t take into account the practices of present followers of Pau Cin Hau’s religion – and thus ignore ‘ethnographic realities’ – which leads them to erroneously conclude that Laipianism is a version of Christianity.

That said, there are certain structural similarities between Laipianism and Christianity. Much like the Christian discourse of healing, Pau Cin Hau articulated the relationship between Pathian and his followers in a framework of healing: he called Pathian ‘the healer of all diseases’ and the religion he was preaching ‘a way of curing sickness’. In some contexts, this characterisation was metaphorical, but elsewhere it was just as much literal. Supplication of Pathian and living according to the teachings of Pau Cin Hau are thought to be genuinely curative. The anthropologist E Pendleton Banks speculated that Pau Cin Hau might have been exposed to the core ideas of Christianity as well as to the healing practices of a travelling missionary physician. ‘Here was a readymade conjunction between monotheism and curing,’ he wrote. Besides, just like Jesus is considered the son of God with healing powers, so is Pau Cin Hau seen as the chosen son of Pathian with power to cure diseases.

To understand the current religious practices of Laipianism, I met with Kam Suan Mang in Siang Sawn. In his late 50s and stockily built, with a round face and black hair, he held the post of Laimang, meaning ‘script king’, the title of the religious head of the Laipian community. He lived in a two-storey brick bungalow painted in pink, with a terrace on the upper storey that offered a commanding view of the village. The walls of his house were filled with several paintings of Pau Cin Hau and framed photos of the Pau Cin Hau script. Kam Suan Mang was chosen as Laimang in 1995 in a series of dreams received by several members of the community.

‘We observe different holidays throughout the year, such as Pathian Saints’ Day [1 December], Pathian Servants’ Day [21 November], Pathian Hymns’ Day [21 February], among others,’ explained Kam Suan Mang. He looked sharp in a white long-sleeve shirt and a longyi decorated in traditional Chin patterns. ‘In Siang Sawn, these days are recognised as holidays, and you can devote yourself to worship. Worship entails singing of hymns composed by Pau Cin Hau and his early followers, and making prayers to Pathian.’ He continued: ‘If you ask me what Pau Cin Hau religion is all about, I’d say it is the faith in Pathian as the almighty creator, and the teachings of his chosen son Laipianpa Pau Cin Hau. In terms of everyday conduct, our beliefs emphasise what we call “holy behaviour” and it entails practising justice, harmony, discipline, peace and hygiene.’

The religion is not related to Christianity by any stretch of imagination although one might find some superficial similarities, he further asserted. ‘We have always been defined [by others] in terms of what we are not, and in relation to Christianity. It is often overlooked that Zo cosmology already had the concept of one God Pathian. It is Christianity that appropriated the concept once it was popularised by Pau Cin Hau.’

Chin society must have seen value in the written technology brought in by the missionaries

Perhaps what makes Laipianism truly unusual (and sets it apart from many other religions – including Christianity – in a peculiar way) is the emphasis placed on the Pau Cin Hau script both as an icon and an index: the script would not only be used to write its scriptures, but pictures or inscriptions of letters from the script would adorn the sect’s places of worship and homes of the followers, just as the Holy Cross adorns Christian churches. In Siang Sawn, as I left Kam Suan Mang’s place on that warm afternoon and walked along the pebbled street in the middle of the village, I noticed that each house had pictures of the script hanging above the door, often accompanied by a picture of Pau Cin Hau.

Writing in 1967, Banks had suggested that Pau Cin Hau’s script is a case of ‘stimulus diffusion’: a local adaptation of the missionary idea of the centrality of the text in preaching the gospel, drawn from the Protestant theological doctrine of ‘sola scriptura’. He tried to theorise Pau Cin Hau’s religion through Anthony F C Wallace’s concept of ‘revitalisation movements’, which are ‘deliberate, conscious, organised efforts by members of a society to create a more satisfying culture.’ Chin society must have seen value in the written technology brought in by the missionaries. Which was why, Banks argues, Pau Cin Hau and his followers adapted the idea of writing and came up with a script of their own. It is worth mentioning that mission activities were essentially centred around acts of translation: in fact, the religion scholars Brainerd Prince and Benrilo Kikon have argued that the mission is translation. Pau Cin Hau understood that – especially the centrality of writing in missionary translation activities. He knew that, if his teachings were to gain the attention of the people, he too needed to have the technology of writing like the colonial missionaries, a wonder that had stirred immense curiosity among many Chin.

There is a popular narrative among Laipian followers that explains what propelled the script to become the central symbol of their religion. It goes like this: when the British administrators and Christian missionaries rendered the Chin language into writing for the first time in the Latin script in the 1890s, Pathian was gravely displeased; and he revealed through Pau Cin Hau the ‘true script’ that can accurately render into writing the tongues of the Chin people.

The terminologies used to describe the hierarchy of the religion also suggest the importance of the script in Laipianism: the highest spiritual position in the community is called Laipianpa, ‘the script creator’, and the next role directly underneath that is Laimang, ‘the script king’. While Laipianpa is a position reserved only for the late founder of the religion, Pau Cin Hau, and no one else can take it, the person to hold the second-highest rank, Laimang, is believed to be chosen by Pathian from time to time.

In the decades following Pau Cin Hau’s death in 1948, Laipianism gradually lost followers to Christianity, the religion that more than 90 per cent of the Chin now follow. The total number of Pau Cin Hau followers has declined from 37,500 in 1931 to around 5,000 today. The historian Pum Kham Pau argues that this shift started once the elites of Chin society started to see Christianity ‘as an alternative source of health and power’. Consequently, it paved the way for the conversion of the common people to Christianity.

The most commonly used illustration of Pau Cin Hau in Laipian religious settings. Courtesy Kam Suan Mang

Today, Chin state remains one of the poorest regions of Myanmar. In a remote mountainous area neglected by the state, Christianity provides a range of services that Laipianism can’t: English-language education, medical care and, to some extent, employment opportunities. These opportunities provided by the Christian churches of various denominations have played a very crucial role in attracting people to Christianity.

In Siang Sawn, Kam Suan Mang and the elders are trying to preserve their faith. In 2013, they published a booklet, History of Pau Cin Hau’s Siang Sawn Religious Sect, outlining the history of the Laipian community in the English language for the first time. ‘The idea behind setting up an exclusive Laipian settlement was to revive the religion and create a spiritual homeland where followers can live according to the teachings of Pau Cin Hau,’ Kam Suan Mang said. One important belief held by the sect is ‘to be in conformity with the passing of time,’ which, he explained to me, means adaptability in the face of challenges. ‘We are open to revising and adjusting our beliefs and practices when necessary to incorporate contemporary values and to be in conformity with the passing of time.’

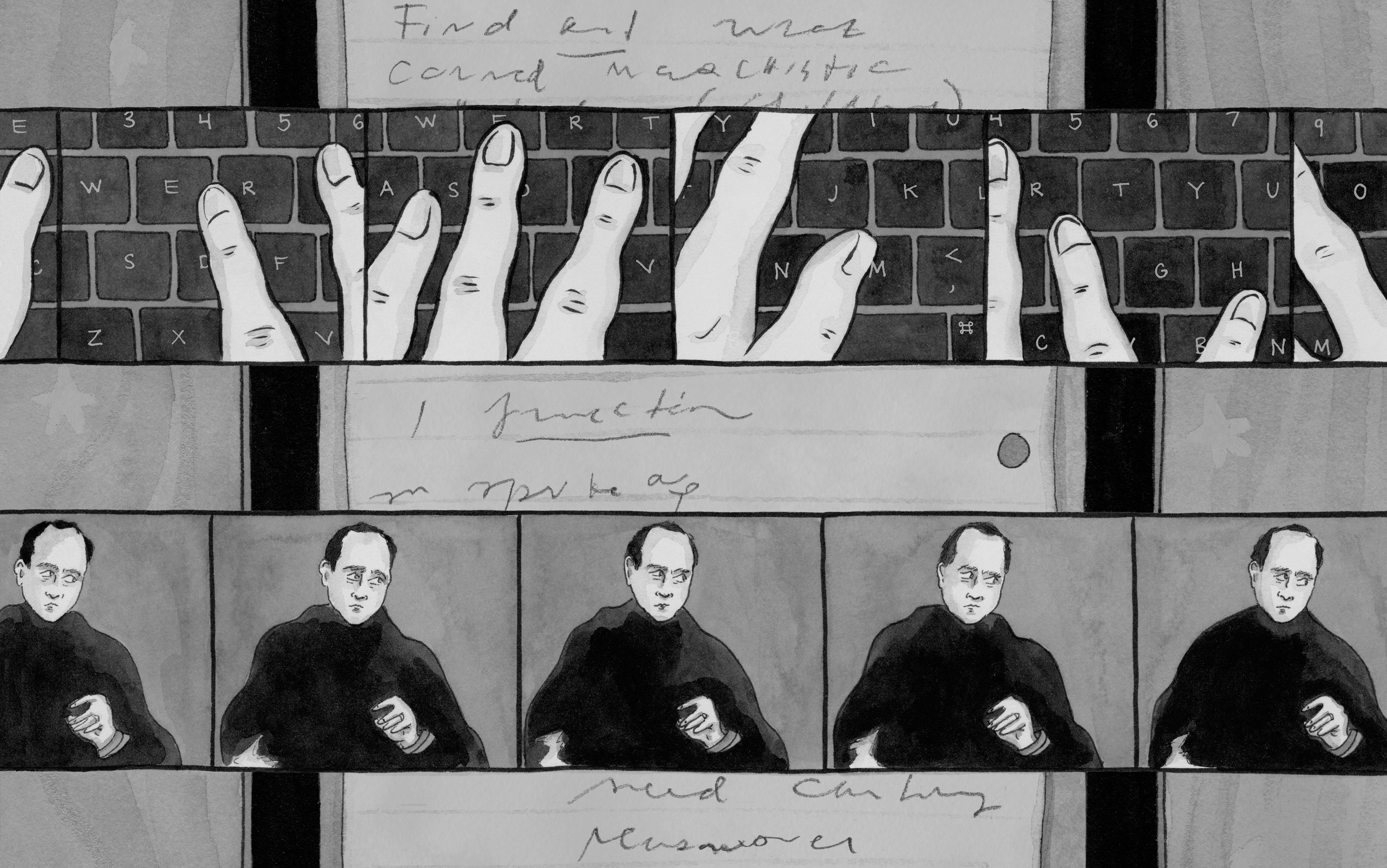

As a silver lining, the Pau Cin Hau script has garnered wider interest among linguists in the past two decades. The script was added to the Unicode Standard in June 2014, and it is increasingly being used by the Laipian community for everyday communication. ‘Now we use Pau Cin Hau lai to write messages on mobile phones, young people use it to make posts on Facebook,’ said Salai Cin Kang, a resident in Siang Sawn. ‘The script has become one of the most visible markers of our identity on digital platforms.’ Kam Suan Mang has some reservations, though. He says this development has a different – and ‘concerning’ – side as well. As people increasingly use the script – the core symbol of the religion – for everyday communication, there is a risk of its losing sacred status, relegating it to a mundane writing system. Quoting the 13th-century Japanese Buddhist philosopher Dōgen Zenji, Kam Suan Mang said: ‘In the mundane, nothing is sacred.’