We read in Rabelais of how the devil took to flight when the woman showed him her vulva.

– from the essay ‘Medusa’s Head’ (1922) by Sigmund Freud

I’m listening to an episode of The New York Times podcast Sway, in which the host, Kara Swisher, interviews the model-turned-writer Emily Ratajkowski about her book, My Body (2021). It’s a probing account of how, possessed of a (highly conventionally beautiful) female body, Ratajkowski negotiates issues of financial independence, control and consent within the omnipresent, all-seeing patriarchy. Having shot to stardom in 2013, dancing half-naked and meowing in a controversial video for the song ‘Blurred Lines’ by Robin Thicke, Ratajkowski describes the validation that came with all the attention she received: how her body increased in value as it was looked at and approved of, especially by men:

All women are objectified and sexualised to some degree, I figured, so I might as well do it on my own terms. I thought that there was power in my ability to choose to do so.

But she’s come to understand that she’s on a ‘spectrum of compromise’; that her body became a valuable commodity only ‘within the confines of a cis-hetero, capitalist, patriarchal world … in which beauty and sex appeal are valued solely through the satisfaction of the male gaze.’

From the conciliatory, almost apologetic tone, you’d have thought Ratajkowski had put her sex kitten days behind her, but her Instagram postbook looks a lot like it did before. What, exactly, had changed? In her interview, Swisher asks if she worries about contributing to the ‘unattainable standard of beauty’ that Instagram promotes. Ratajkowski agrees that it can be a ‘toxic’ place, but thinks it shouldn’t be up to her alone to change this – that the culture needs to think collectively, systematically, about the way it looks at women:

That’s just not my politics. It’s sort of like, you know, if I dress differently, then girls won’t think that they have to show their boobs in a shirt … I think that it again puts so much pressure on young women to kind of change the system. And, you know, it turns women against each other as well, in a way that I don’t like … I want to look at the larger cultural framework.

To some extent, she’s right. If Ratajkowski stops promoting a certain version of femininity on Instagram, it won’t make much difference to how capitalism exploits and abuses the bodies and minds of young women. Mega-platforms such as Instagram and Facebook hold far greater responsibility than she does. But, however much Ratajkowski allows for certain ambiguities in the way she exploits her own body, there is an implacability to her position. She cites sex workers as an example of women commodifying their bodies for survival, pleasure or control, saying she feels similarly about ‘girls and social media’:

I’m like, go get it, honey; if that’s what you want to do in the system that we live in. I’m not going to tell you not to.

This is what her critics find difficult to get around: her awareness of the limitations of ‘female empowerment’ and her insistence, nevertheless, on Go get it girl as a modus operandi. But I wonder whether Ratajkowski’s Instagram itself isn’t, in a subtle way, asking us to think critically about the way we look at images of beautiful women – of beauty, full stop?

When Ratajkowski’s book was published, I found myself thinking back to the debates around the representation of the female form that took place in feminist circles in the 1970s and ’80s, which form the subject of the book I had just finished drafting, Art Monsters (forthcoming in 2023). The link is not too far-fetched; Ratajkowski even quotes John Berger’s Ways of Seeing (1972):

You painted a naked woman because you enjoyed looking at her, you put a mirror in her hand and you called the painting ‘Vanity’, thus morally condemning the woman whose nakedness you had depicted for your own pleasure. The real function of the mirror was otherwise. It was to make the woman connive in treating herself as, first and foremost, a sight.

Important and influential as Berger’s book has been, he was drawing on the points being made by a group of feminist artists and activists, who called for a complete overhaul in the way we look at art, asking to be acknowledged as both the subject and the producer of their own work. These artists reclaimed their naked bodies and tested how those bodies upset people or invited certain ideas around submission, narcissism, prudery, modesty, exhibitionism, sex work, body-shaming, normativity, conventionality. They were clawing back their bodies from patriarchal control. But they, too, ran into resistance – feminist, as well as patriarchal.

Throughout the 1970s and into the ’80s, there was a backlash against this kind of reclaiming of the naked body, from feminist polemicists campaigning against pornography, to feminist artists and critics who were concerned that any image of a nude woman would play right into the male gaze. I am deeply troubled by these interdictions, and the way they made the female body unrepresentable. Now as then, the same debates are playing out over the way women represent their bodies. What exactly, I wondered, listening to Swisher’s podcast, do we want from Ratajkowski? Do we want her to get fat, wear baggier clothes, stop taking selfies and start Instagramming her lunch? Do we want her to storm the offices of Facebook and pull the plug on Instagram? Burn herself in effigy in downtown LA?

Or do we want her to just go away, so we stop having to look at her, in all her poreless, tightly toned beauty?

‘Can an art historian be a naked woman?’ she’d wanted to ask

In a 1990s documentary about feminist art in the United States, Carolee Schneemann reflects that one of the central puzzles of her life as an artist has been the problem of being an image-maker in possession of a gendered body, historically ‘interred’ as image. As an image of Diego Velázquez’s Rokeby Venus (1647-51) appears on the screen, she asks, in voiceover, how she could possibly ‘have authority in a culture where there was no pronoun that had any authority in those years except he: the artist he, the student he …’

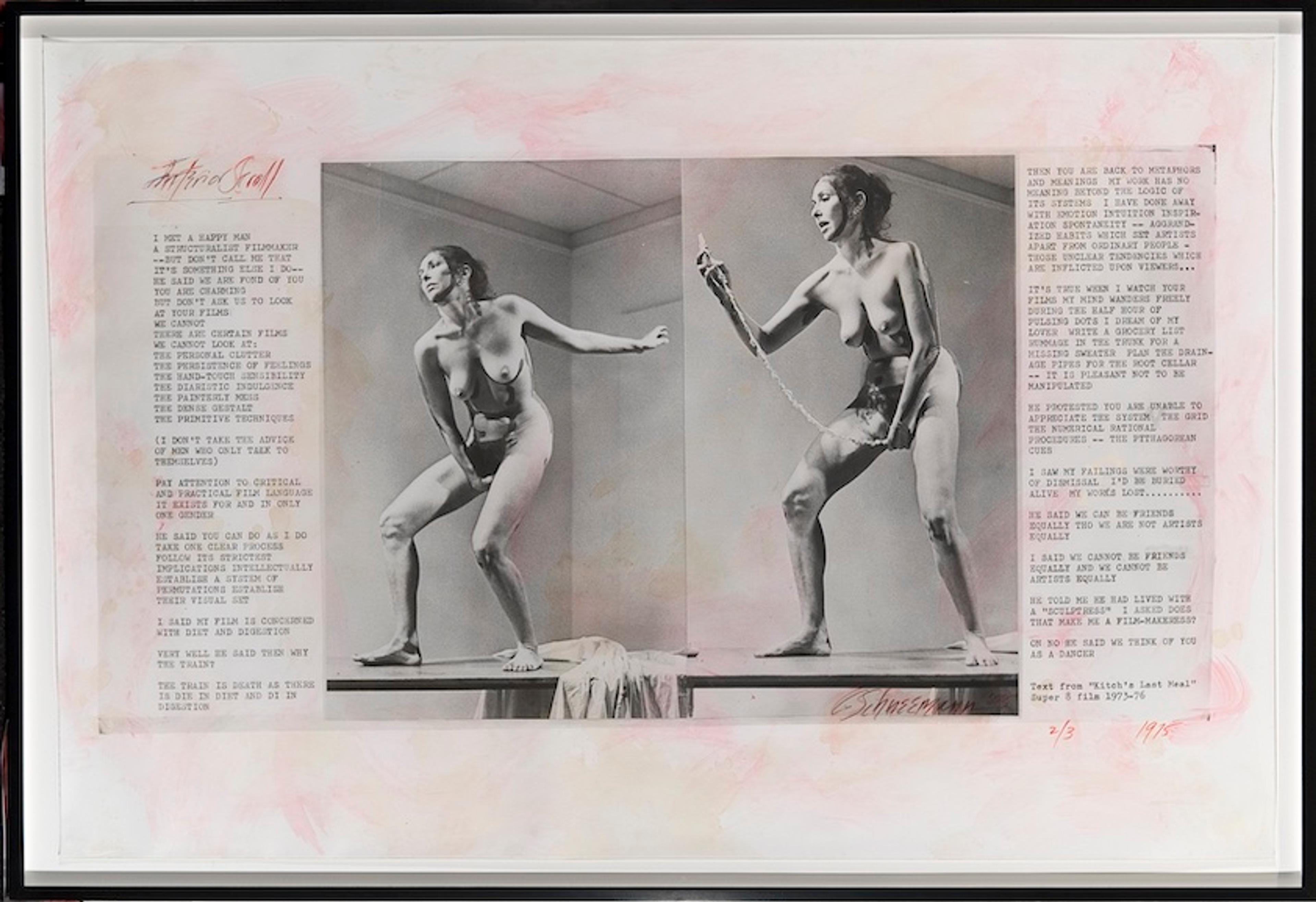

Schneemann had been on the frontlines of the fight for female artists to be taken as seriously as their male counterparts, making confronting work that figured the female body as both the subject of and the means by which art was produced. In her notorious performance Interior Scroll (1975), she pulls a long, rolled-up piece of paper from her vagina; printed on it is a feminist screed from which she then reads aloud. In Up to and Including Her Limits (1973-6), she records herself swinging naked from a tree surgeon’s harness, holding a crayon and letting the movement of her body create the lines on the paper. And in her earlier Naked Action Lecture (1968), she stripped while giving a slide lecture on art history. ‘Can an art historian be a naked woman?’ she later said she’d wanted to ask.

Interior Scroll (1975) by Carolee Schneemann. © Carolee Schneemann. ARS/Copyright Agency, 2022

Schneemann, and other feminist artists who challenged the art world in the 1960s and ’70s, were specifically concerned about the meanings projected onto the female body: beautiful, ugly, pure, unclean. (Recall Tertullian: ‘Woman [is] a temple built over a sewer.’) In the essay ‘The Obscene Body/Politic’ (1991), Schneemann argued that, in the 1960s and ’70s, women had barged into the art world, driven by several millennia’s worth of anger at being sidelined, sexualised and idealised in images and sculptures, while their actual bodies were characterised as ‘defiling, stinking, contaminating’. If women artists of her generation turned to ‘erotic imagery’, it was because, she said, ‘our bodies exemplify a historic battleground’.

As an undergraduate at Bard College in New York, lacking access to nude models, Schneemann had painted her naked boyfriend while he slept, as well as herself without clothes, and was summarily sent on a leave of absence. (‘No objections were raised to her posing nude for her fellow male painting students,’ notes the curator Sabine Breitwieser.) And when she included her clitoris in the ‘Eye Body’ photographs, the art world recoiled, asking: ‘Why is it in the art world rather than a “porno” world?’ The clitoris was one part of the female body, it seemed, that needed to be left out of the art frame, and included in the pornographic frame instead. Ob-scene, a word with varied roots, possibly derived from ob- (in front of) and -caenum, filth. The unseeable parts of the female body are, in art, in the wrong place – ‘matter out of place’, in the anthropologist Mary Douglas’s definition of dirt and impurity.

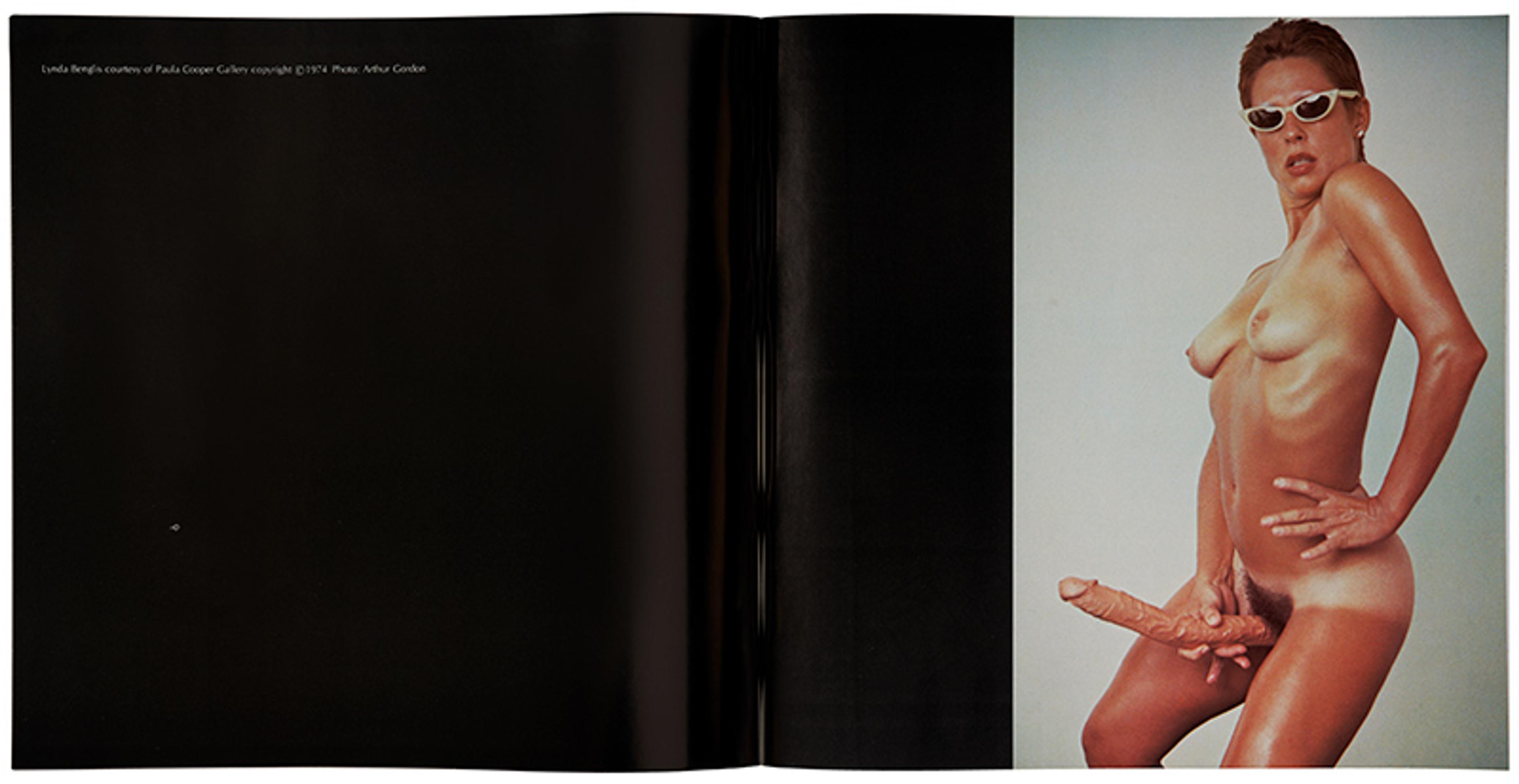

Schneemann’s essay puts me in mind of the controversy, erupting in 1974, over the artist Lynda Benglis’s advertisement for an upcoming show placed in the journal Artforum. It depicted the artist herself, naked except for a pair of cat-eye, white sunglasses, holding an enormous double-headed dildo against her crotch. (She would later make five casts of this dildo – in bronze, in lead, in aluminium, in tin – for works called Parenthesis and Smile.) The ad spread across two pages, just like a Playboy centrefold. Benglis called it the ‘ultimate mockery of the pinup and the macho’ – a blatant retort to an art world that wanted to see a female nude only as a sex object or an art object, but never as an agent with a sense of humour. Five of the magazine’s editors were incensed; publishing a letter in the following issue, they called the ad an ‘object of extreme vulgarity’. To them, it was obscene, pornographic, by which they meant: This is out of place, it does not belong in our magazine.

Lynda Benglis Artforum advertisement, Artforum, November 1974 10 1/2 x 21 x 1/8 in. Photo: Melissa Goodwin, Courtesy Pace Gallery © Lynda Benglis. ARS/Copyright Agency, 2022

In Rabelais and His World (1965), the literary critic Mikhail Bakhtin contrasted the classical body – perfected, clean, polished and associated with high art (and, it goes without saying, white) – with the grotesque – the open, filthy, changeable body that belongs with low forms of entertainment: parody, buffoonery, carnival, feasts of the fool, folk culture. For Bakhtin, classicism is the mind, sublime and transcendent, while the grotesque concerns itself with ‘copulation, pregnancy, birth, growth, old age, disintegration, dismemberment’. The grotesque body is not separate from the world but in a state of exchange with it:

it is unfinished, outgrows itself, transgresses its own limits. The stress is laid on those parts of the body that are open to the outside world … on the apertures or the convexities … : the open mouth, the genital organs, the breasts, the phallus, the potbelly, the nose.

Bakhtin doesn’t hold one body superior to the other. But it’s clear what constraints the classical body places on the female form, and what liberations the grotesque might offer. Where the classical female body is masterable in its (supposed) wholeness (where is the clitoris!), the grotesque erotic body, experienced in fragments, is always escaping into the unknowable, the uncontrollable.

Benglis’s Artforum ad inverted the relationship between Bakhtin’s two registers, offering the viewer a smoothness, hairlessness and plasticity that is classical in form but grotesque in affect. In her 1992 study of the female nude in art history, Lynda Nead notes that ‘the classical forms of art perform a kind of magical regulation of the female body, containing it and momentarily repairing the orifices and tears.’ The feminist obscene body disturbs art history’s ‘magical regulation’, collapsing the classical and the grotesque body into one. By, as it were, ‘putting us in front of filth’, Benglis confronts the viewer with what might usually be exiled to the realm of pornography and worse: not to the kind of tasteful art-cum-pornography belonging to a Sadeian, Bataillean heritage, but to a debased – read, working-class – American buffoonery. Not the avant garde of perverse sexuality, but the grotesque realm of the girlie mag. Benglis is hip to this: her masterstroke being to present the image not as art, but as advertisement.

That tan, the oiled skin, the sunglasses! It has all the hue and subtlety of a car-wash calendar

Writing in Artforum many years later, the art historian Richard Meyer said:

But if the ad is regularly displayed and reprinted, this is not to say that it is closely considered or fully reckoned with … ‘An object of extreme vulgarity’ seems to me closer to the mark, in part because it retains some sense of its confrontation with both art and feminism in 1974.

The image is vulgar – loud and slick and tacky. That tan, the oiled skin, the sunglasses! It has all the hue and subtlety of a car-wash calendar. Aesthetically speaking, there is nothing to redeem about it. It just wants to get in your face. But there is a pop queer erotics at work here that is one of the most salient challenges the image levels at the viewer: between the short hair and full pout, she looks like some dude heartthrob in a teen magazine. It is clearly an attempt to wrong-foot people’s expectations about the ‘female’ body, what it should look like, what attributes it should have. And it gives female desire the characteristics that have been attributed to male desire – aggressive, phallic. It turns machismo into a myth, as well as feminine passivity.

Benglis’s ad strikes me as not that far removed from Ratajkowski’s turn in the Thicke video, which was almost universally slammed: at best, for reinforcing icky stereotypes in which the men are clothed individuals and the women are naked playthings (the Déjeuner sur l’herbe critique, if you will); and, at worst, for defending rape culture (the ‘I know you want it’ critique). Ratajkowski writes in her book about how, at first, the video seemed tacky and she wasn’t interested (the vibe they were going for, according to the treatment, was ‘TRUE PIMP SWAG’/‘NAKED GIRLS XXX’ although, whoever wrote this noted, ‘THIS IS FAR FROM MASOGYNIST’ [sic]). But when Ratajkowski heard the director was a woman, and – importantly – when her fee was raised, she agreed to do it.

If this video had to exist, I’m glad she’s in it. The other two girls, Jessi M’Bengue and Elle Evans, gamely play along; they are beautiful and thin, and they can frolic and dance, but Ratajkowski has presence. There’s thought behind the eyes; a spark, an individual will. She mugs and poses and plays with farm animals, but at one point she flat-out rolls her eyes at Thicke’s lecherous antics. (She also alleges in the article that he groped her bare breasts during filming.) And that one moment is the tear in the image, the punctum that undoes the whole composition.

It’s a very troubling video, but some of the critiques launched at it unconsciously reproduce the way it objectifies the girls. One YouTube monologue decries the video because it has models ‘who prance around like objects’; one blog post refers to the models ‘used in the video’ and its author advises against even watching the uncensored cut, where the girls are fully naked, ‘as it really is too disgusting’.

What if, as Ratajkowski maintained for years after the video came out, the girls weren’t being taken advantage of, but were professional dancers getting paid for a day’s work? Though I don’t condone the video on any level – as power imbalance, artefact of rape culture and certainly not as the unsafe work environment it clearly was – it’s important not to forget that the women were there of their own volition. They’ve bought into a hegemonic version of femininity from which they profit (and other women suffer). Perhaps this underpinning of commercial exchange explains the unease some have felt with the video? The girls are quite literally selling their bodies – because, as models and dancers, the body is their medium. As in Benglis’s advertisement – where her body is the art and the commodity – seeing the girls as skilled performers being paid for their time runs right against the myth of the male genius artist, labouring at his craft in obscurity, struggling to support himself, getting paid for his canvases when he can, then dying unknown.

Benglis’s ad divided feminists. The art critic Lucy Lippard saw it as a ‘successful display of the various ways in which woman is used and therefore can use herself as a political sex object in the art world,’ while the Feminist Art Journal’s founder Cindy Nemser called it ‘another means of manipulating men through the exploitation of female sexuality.’

I understand Nemser’s discomfort. Feminism was a tenuous movement at the time. It needed supporters: it needed its practitioners not to do things to fuel the anti-feminists’ fire. But you didn’t have to oil yourself up and pose with a dildo to be accused of exploiting female sexuality in 1974. Earlier that year, the artist Hannah Wilke began to use her naked body in her work. In S.O.S. Starification Object Series (1974-75), she strikes a number of poses, in the fashion-plate style, while naked from the waist up. They’re so over the top, it feels like falling for a prank to describe them, but let me try: rollers in her hair, straddling a chair, pouting. Rollers in her hair, shirt gaping open, fingers lightly touching her lips. Topless, an arm of her sunglasses resting on her lower teeth, fuck-me eyes. Topless, in sunglasses and a cowboy hat, holding a pair of toy guns in her hands, bang-bang!

Centre-Pompidou-Paris-c-Scharlatt-VAGA-at-ARS-New-York-.jpg?width=3840&quality=75&format=auto)

Hannah Wilke, S.O.S. Starification Object Series: An Adult Game of Mastication (1974-75), mixed media installation (detail). Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris. Courtesy and © Marsie, Emanuelle, Damon, and Andrew Scharlatt, Hannah Wilke Collection & Archive, Los Angeles. Artists Rights Society. ARS/Copyright Agency, 2022.

The images are cringeworthy, but that’s exactly the point. They remind me of that ‘women laughing alone with salad’ meme, in which the women beam into their lettuce, smile at their strawberries, throw their heads back and laugh at a floret of broccoli speared on a fork. They are hegemonic poses of exaggerated unreal joy. Wilke’s photographs knowingly, mockingly adopt this Be like me, girls attitude. In a way, they are as hard to look at as the cancer photos she would take at the end of her life, depicting her beautiful body bloated and suffering.

To me, a feminist who came of age in the ironic 1990s, it’s clear the S.O.S. images are not meant to be read straight. But when the photos were shown at that delicate mid-1970s moment when feminists had to get their message just right, Wilke was accused of narcissism, vulgarity, gratuitous nudity – of courting the straight male gaze, and thwarting the female one.

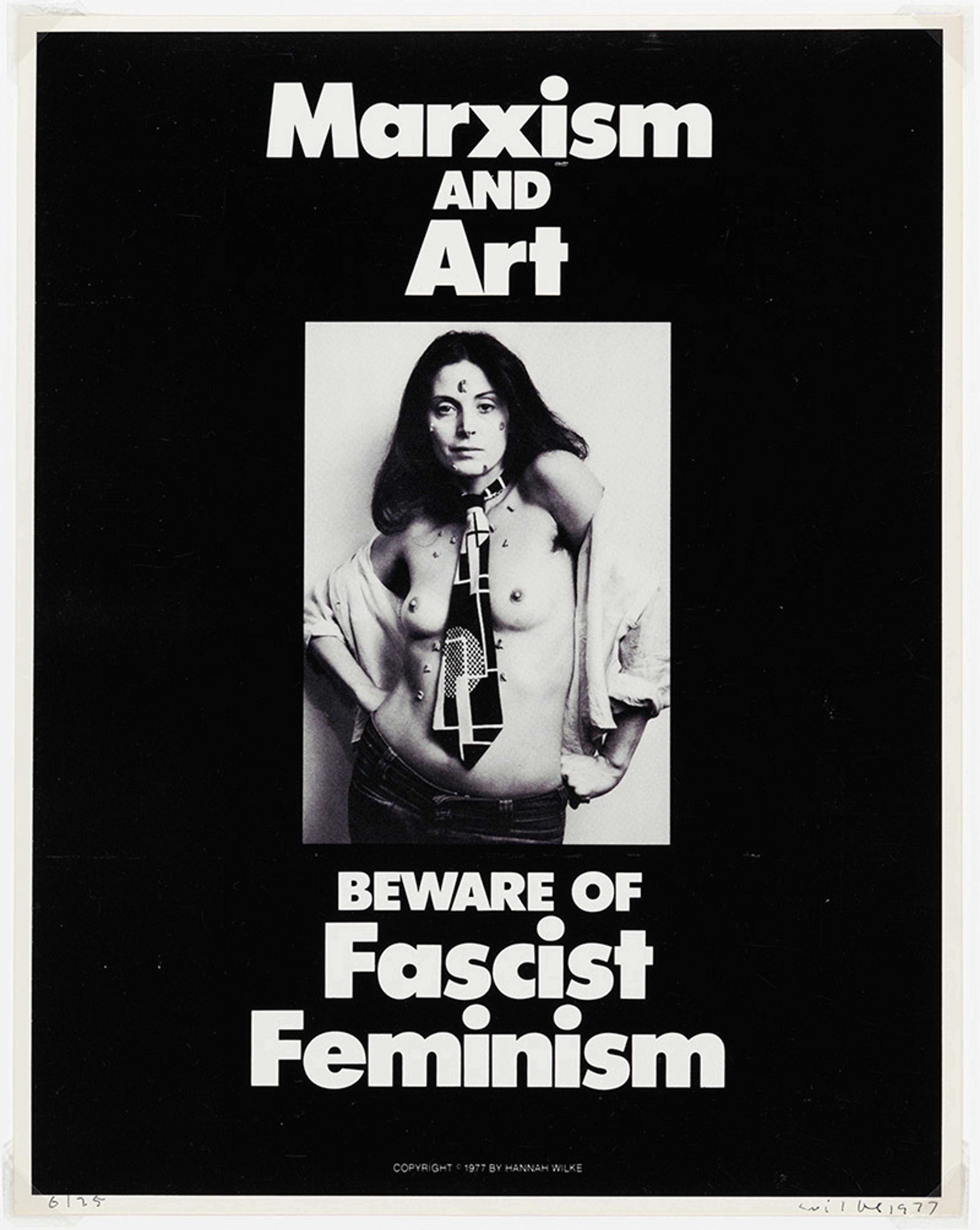

In 1977, Wilke made a poster of herself wearing a man’s tie and little else, under which was printed the slogan ‘BEWARE OF FASCIST FEMINISM’. Beware of fascist feminism. I’m habitually intrigued by internecine strife among feminists: the way certain conflicts can make the broad church of feminism feel like a single pew in which we’re all jostling for a seat. Feminism is less a cohesive movement than a series of concerns that sometimes overlap, yet just as frequently fail to catch us all, and they fragment just as we need them to hold us together.

Hannah Wilke, Marxism & Art: Beware of Fascist Feminism (1977), offset poster. © Marsie, Emanuelle, Damon and Andrew Scharlatt, Hannah Wilke Collection & Archive, Los Angeles. Artists Rights Society. ARS/Copyright Agency, 2022. Image courtesy Tate Gallery, London.

Wilke was responding, no doubt, to Lippard’s essay ‘The Pains and Pleasures of Rebirth: Women’s Body Art’ (1976), in which she worried that for female artists to show themselves naked was not always as radical a gesture as they may have intended: ‘[T]here are ways and ways of using one’s own body, and women have not always avoided self-exploitation.’ She confessed to not having much ‘sympathy’ for ‘women who have themselves photographed in black stockings, garter belts, boots, with bare breasts, bananas, and coy, come-hither glances.’ Even if it’s in the service of parody, ‘the artist rarely seems to get the last laugh.’ She is watching the men to see how they respond, and the men are laughing.

Can one not be flirt and feminist, beautiful woman and artist, without being judged ‘confused’?

Writing in Screen magazine in 1980, the film critics Judith Barry and Sandy Flitterman-Lewis called out the body art of the 1970s, accusing it of practising the ‘glorification’ of an ‘essential female power … residing somewhere in the body of women.’ Leaning on Laura Mulvey’s influential essay ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’ (1975) about narcissism, film and the male gaze, they wrote: ‘While we recognise the value of certain forms of radical political art … this kind of work, if untheorised, can only have limited results.’ Their article would decisively mark off the 1980s from the ’70s as far as feminist art was concerned; to one side, there were the feminist body artists, ‘untheorised’ and ‘essentialist’. On the other, artists whose approach was more psychoanalytic and poststructuralist, such as Martha Rosler (Semiotics of the Kitchen, 1975) or Mary Kelly (Post-Partum Document, 1973-79). The pair judged Wilke harshly: ‘It seems her work ends up by reinforcing what it intends to subvert.’ They insisted that personal experience ‘must be taken beyond consciously felt and articulated needs of women if a real transformation of the structures of women’s oppression is to occur.’

According to their form of iconoclasm, the female body – nude or clothed – could not be represented without upholding the male gaze and all the violence and erasure of agency that could imply. By 1981, when Andrea Dworkin’s watershed manifesto Pornography: Men Possessing Women was published, the idea that ‘pornography is violence’ had become ‘doctrine’ (though not uncontroversially among sex-positive feminists). In 1982, Kelly told the US artist Paul Smith:

when the image of the woman is used in a work of art, that is, when her body is given as a signifier, it becomes extremely problematic. Most women artists who have presented themselves in some way, visibly, in their work have been unable to find the kind of distancing devices which would cut across the predominant representations of woman as object of the look, or question the notion of femininity as a pre-given entity.

The filmmaker and theorist Peter Gidal would go even further: ‘I do not see how … there is any possibility of using the image of a naked woman … other than in an absolutely sexist and politically repressive patriarchal way at this conjuncture.’

In the abstract, I take his point; in any case, for a male filmmaker, there are different politics of portrayal at play. But to conclude that the female body cannot be shown is to wall it off in a kind of politically correct purdah, unrepresentable: it’s as essentialist and reductive as anything the 1970s feminists said. It aligns feminist critique with the Law of Moses: ruling out images of God, which would only ever be false idols. It both elevates and makes the female body invisible: unrepresentable, un-seeable, obscene.

What a culture – even a feminist one – finds ‘problematic’ about images of nude women is an integral part of how it thinks about and constructs gender, argued Nead in 1983, in the midst of these debates. Part of the project of feminism was to question and disavow an outdated, mindlessly obedient femininity. Art that seemed to further its values of prettiness, pleasingness, pleasure was politically questionable; in some quarters, it could only scan as reactionary, or narcissistic. But that was precisely what Wilke was interrogating. Female narcissism is dangerous to the patriarchy, the art historian Amelia Jones speculates, because it has no need of the desiring male subject’s desire, or approval.

The feminists accusing Wilke of being in thrall to the male gaze couldn’t prevent themselves from reproducing restrictive ways of looking at the female body. Can one not be flirt and feminist, beautiful woman and artist, without being judged ‘confused’? Despite their best intentions, these feminist critics could not find a way to think through, along with Wilke, the complexity of ‘beauty’, pleasure or the desire to look, within a feminist framework. ‘There was more than a hint of Warhol in her deployment of her own glamour,’ notes Nancy Princenthal. Why is Warhol’s self-fashioning art, while Wilke’s is narcissism? Narcissus was a boy but it’s the girls who get smeared with his name.

However ‘natural’ Wilke’s body might appear in the S.O.S. series to an audience accustomed to seeing similar pictures in magazines where they’re being sold something, from depilatory cream to an idea of how a woman should look, it has in fact been lit, posed, processed, developed, just as in our day it would be Photoshopped. The problem – for Schneemann, Benglis and Wilke, as for Ratajkowski – is how can the aestheticised body find a way to, in Berger’s terms, act as well as appear?

There are all sorts of cues in Wilke’s photographs to remind us that these images are constructed – most glaringly, the little chewing gum vulvas stuck all over her torso and face (helpfully masticated by audience members at her live performances). They reference the toothy vagina dentata; the cunt as scar, as wound. Chewing gum was the perfect metaphor, said Wilke, for the way women were treated in US society: ‘chew her up, get what you want out of her, throw her out and pop in a new piece.’ The vulvas were a frequent motif in her work. Another, earlier project consisted of hundreds and hundreds of labial sculptures – tiny and cute; larger and more abstract; scalloped in pink latex and affixed to the wall. Wilke made scores of them in a variety of materials associated with domesticity, including clay, gum, Play-Doh, even dryer lint (salvaged from laundry she’d done for her partner Claes Oldenburg). Her association of genitalia with gender is of its time, but that doesn’t limit the potential ways of reading her sculptures. I don’t know what her gender politics would be today, but it is inarguable that she presents the pussy as something quite literally constructed, something that could be owned or given. It was her mission ‘to wipe out the prejudices, aggression, and fear associated with the negative connotations of pussy, cunt, box.’

The pussy is political. The starification in the title of Wilke’s S.O.S. series plays on the word scarification, referencing African and Polynesian tribal rituals in which scarring is part of a process of beautification. The ‘scars’ are symbolic, performative, literally signifying at skin level. With her play on words, perhaps Wilke is suggesting Western women scar their own bodies, so to speak, in order to meet Western beauty standards. But chewing-gum cunts are a reference, as well, to more sinister scarring practices: ‘Remember that as a Jew, during the war,’ Wilke wrote, ‘I would have been branded and buried had I not been born in America.’ Remember, too, the internal scars borne not only by those who went to the camps, but by their descendants or distant family who didn’t; the scars of diasporic guilt; the scars of violence further back, villages erased in pogroms, desperate flights to the US. All of this, compacted into little cunts made of chewing gum.

Wilke was exploring form itself, questioning its basic components. The original idea was to create a very simple structure, moving so quickly from a ‘flat painterly surface’ to a three-dimensional form that it’s almost a ‘gestural motion’, she told Nemser. The fact of each piece being a gesture is, Wilke said, more important than its being a ‘cunt’. This is important: Wilke is not operating solely in the realm of figuration, but of movement and embodiment. She was, after all, a sculptor by training, and this is how I think of S.O.S.: as a series of sculptures, using, instead of gum or lint, herself as the medium.

Once upon a time, even feminist critics didn’t know what to make of feminist body art

By posing in the register of the classical rather than the grotesque, Wilke was trying to show that women could make art as well as be art – and that the female body had to be reclaimed from capitalism. It may be reading too much into the series to imagine Wilke was commenting on the construction of white femininity, but she was certainly trying to comment on the ways women’s bodies are bought and sold in postwar US culture. The trouble was, her critics couldn’t see the distance between what she was doing and what she was critiquing. All they saw was a conventionally attractive body. Wilke recalled, years later:

I had a woman come into the gallery and say ‘Oh, you’re the model.’ And I said ‘Yes, I’m the model – and I’m also the artist. This is my show.’ She didn’t expect this.

How would Wilke’s work have been received, I wonder, if she hadn’t been a complete knock-out, so perfectly aligned with the beauty standards of her time? Would the work have read as more radical? Lippard admits that women artists who ‘happen to be physically well-endowed probably come in for more punishment in the long run.’ But she can’t prevent herself from lobbing her own feminist grenades, calling Wilke ‘a glamour girl’ who ‘sees her art as “seduction”’, someone who has confused ‘her roles as beautiful woman and artist, as flirt and feminist’. Later in life, Lippard recanted, explaining that when she wrote that essay she was in her ‘combat boot period’ and that Wilke ‘constantly preening’ rubbed her up the wrong way. It is instructive to remember that, once upon a time, even feminist critics didn’t know what to make of feminist body art.

The problem of Wilke is the problem of beauty for feminism. When she was beautiful, they told her to stop taking her clothes off. When she was dying, they applauded the bravery of taking off her clothes. She was not a better artist when she was dying. She was not a better artist for having experienced pain and despair. If that is our standard, then we have not at all moved past the Romantic ideal of the suffering, isolated male genius poet-painter.

Beauty is a poison pill. Beauty makes us sick, makes us spend all our money, makes us sad and desperate. It is no wonder so many feminist artists have turned to ugliness, abjection and roughness, in order to be taken seriously. But Wilke urged women to

take control of and have pride in the sensuality of their own bodies and create a sensuality in their own terms, without referring to the concepts degenerated by culture … to touch, to smile, to feel, to flirt, to state, to insist on the feelings of the flesh, its inspiration, its advice, its warning, its mystery.

What I take from Wilke’s work is the way it urges women to redefine ‘sensuality’ according to their own sensibilities, and to insist on haptic perception as a means of clearing out internalised misogyny. It suggests that a feminist erotics of art is one that attends to surfaces, non-hierarchically: ‘The internal scars,’ as she pointed out, ‘really don’t show.’

The critic Janet Wolff writes: ‘[T]here is no “correct” feminist aesthetic.’ Wilke’s body, Schneemann’s body, Benglis’s body, and the things they did with them, made a lot of people uncomfortable. As they should. Art needs to put us on edge in order to move us towards new ways of thinking about gender and the body, about race, class and identity. There’s no escaping the patriarchal meanings of the female body, or recovering a neutral female body, as Nead asserts, ‘but signs and values can be transformed and different identities can be set in place.’ This is the work of the art monster, I argue: to dream in new languages new ways of living in the body.

Ratajkowski understands that we cannot escape the patriarchal gaze, but that it is possible to borrow its visual language to subvert its values. Looking at Ratajkowski’s Instagram, I notice funny things: an image that looks like different pictures of her, pasted on top of one another on the same billboard, the different layers tearing away, exposing different versions of Emily. Or how one series of photos has her suggestively holding a raspberry up to her teeth, then we cut to a burrito slathered in cheese and sauce, then we’re back to Ratajkowski, the raspberry, and a bit of side-eye. I don’t think she’s just asking us to think about how she can’t eat burritos, only raspberries; I think it’s a bit of surrealism.

A feminist aesthetics of monstrosity braves dismissal to explore difficult truths

An earlier slide shows her baby’s feet, held up to a mirror. The slides begin and end with Ratajkowski in extreme close-up, wearing a houndstooth blazer and with a massive honking diamond on her finger: in the first one, she looks doe-like at the camera; in the last, her eyes are closed. There’s a lot going on here in terms of the gaze, the dreaminess of those baby feet, the luscious berry in that Victoria’s Secret-style pose, all the doubling. Perhaps we can think of these moments in the context of Kelly’s ‘distancing devices’, updated for the Instagram generation. I’m reminded that Ratajkowski (whose father is an art teacher) was a one-time art student. I would not be surprised if, on some level, she regarded all of it as an elaborate performance piece.

In Art Monsters, I’ve ended up tracking a single comment articulated by Virginia Woolf in 1931 across the ensuing decades of feminist art and literature:

These were two of the adventures of my professional life. The first – killing the Angel in the House – I think I solved. She died. But the second, telling the truth about my own experiences as a body, I do not think I solved. I doubt that any woman has solved it yet.

The truth about our experiences as bodies is a material one that leaps off the page or the canvas to touch the viewer/reader: this reads to me as a feminist aesthetics of monstrosity, that braves dismissal to explore difficult truths. What might look like narcissism in the conventional sense of the term is an attempt to touch the other through imaging the self. Such images work towards a collapsing of the subject and the object, fiction and nonfiction. ‘What if,’ the artist Eleanor Antin asked in 1974, ‘the artist makes the leap from “the body” to “my body”?’ What happens then?

These questions were unresolved then and they’re still open today. What the feminists of the 1970s and the backlash of the ’80s tell us is that we have to be good lookers. We must keep looking consciously and with intention for the impossibly thin distance between what we see, and what it might begin to mean.