Over the course of the Second World War, approximately 45,000 psychiatric patients died of starvation and disease in France, imprisoned in hospitals that were supposed to care for them. In 1979, one psychiatrist was interviewed by a newspaper about what he had witnessed during that time:

It was a terrible period at the hospital. The food supplies we received were completely insufficient for feeding 3,000 sick people. I lived through scenes as terrible as those in the concentration camps. Patients were chewing their fingers off … They drank their own urine, ate their faeces, this was common.

In the late 1980s, when this calamity finally came to public attention, there was a flurry of recriminations. Some commentators blamed the psychiatrists, calling out a professional conspiracy of cowardice and neglect, while others suggested that the deaths were driven by an official policy of extermination by the Vichy government and Nazi central command. Exhaustive historical research has so far failed to support either of these theories.

There was one hospital that defied the catastrophe. In 1941, when the national mortality rate for psychiatric patients had tripled and around the time when some institutions were losing more than 40 per cent of their population, the hospital at Saint-Alban-sur-Limagnole, in southern France, had a death rate of less than 10 per cent – and no deaths from malnutrition.

Growing up in Britain in the 1980s, the Second World War seemed far removed from my experience. I was taught that fascism had been defeated, democracy and equality had won. But a different picture emerged in my mid-20s, when I moved to east London and began working in a community for people marginalised because of neurological disabilities. I witnessed startling poverty and exclusion, and civic systems that seemed on the brink of collapse. I supported clients through relentless benefits assessments with state employees who appeared trapped in the role of hostile gatekeepers. I attended medical appointments with doctors who behaved like automata, hurriedly citing the ‘evidence base’ and leaving my clients to make life-or-death decisions without specialist support. And I was alarmed by the number of times, in a just a few years, that I attended clients’ funerals when they died early, preventable deaths.

Some of us involved in this work came to see political forces as the real and greater enemy – to realise that clients and staff alike were locked into logics from which we all needed to be emancipated. But we didn’t act decisively enough. There were always other priorities and the changes we needed were hard to identify. I remember many times when I wished we had an example to learn from.

I came across the story of Saint-Alban too late for my work in London. When I did, it felt like a message of hope tucked into a time capsule: this is what you were trying to do. It shows us the roles that institutions can play, both good and bad, in fighting or reinforcing everyday fascism, and reveals how our attitudes towards madness are an index for our beliefs about human potential as a whole.

Saint-Alban possessed a number of practical advantages that helped it shield its residents during the war. It was relatively small, with a population of 540. Secondly, its rural location meant that it was close to sources of food, while being at a greater remove from the scrutiny of the Vichy administration.

But if Saint-Alban benefitted from being overlooked, it suffered from being desperately poor. As late as 1939, its building, a medieval castle, had little plumbing, heating or sanitation. Many patients slept on straw beds in locked cells. Some occupied stables still used by livestock. Formerly a Catholic sanatorium, it was run by a combination of nuns and wardens with a single doctor, named Paul Balvet, in charge. And the expectations were desperately low. ‘All I had been taught,’ Balvet would later comment, ‘was to make sure there were no crimes, no pregnancies and no escapes.’

When war broke out, Saint-Alban lost 36 staff members to the draft, and its population grew to more than 850 as patients were displaced from hospitals being requisitioned elsewhere. (We know that the Catholic sisterhood remained in residence and continued to play a central role, but their stories, if they were ever recorded, have been difficult for me to locate.) In need of help, Balvet approached the internment camp at Septfonds, some 200 km southwest of Saint-Alban, seeking anyone with relevant experience. The camp had been established to accommodate political refugees fleeing the Franco regime after the Spanish Civil War, and Balvet was pessimistic about finding anyone useful among all these ‘Reds’ and ‘criminals’.

The 27-year-old Catalan François Tosquelles was one such ‘Red’ who was also a qualified psychiatrist. He’d fought among the antifascist militias during the civil war and had run a psychiatric clinic for combatants on the battle front, fleeing across the border after the collapse of the republic. When Balvet found him at Septfonds, Tosquelles was running another clinic ‘in the mud’, under conditions of starvation.

A prewar photo of François Tosquelles (far left) with patients of the Pere Mata institute in Reus, Catalonia, on a trip to the seaside. Photo courtesy the Archives of the Tosquelles Family

‘I learned half what I know about psychiatry from Tosquelles,’ Balvet would later say. Tosquelles’s background had equipped him with a pragmatic attitude and a strong suspicion of authority. I suspect it also gave him a clarity of vision that was lacking among his French counterparts at the time: unlike Balvet, he already knew what fascism looked like at close quarters, and how bad things might get.

On Tosquelles’s arrival at Saint-Alban in January 1940, he and Balvet set about recruiting everyone at hand to the task of finding food. Patients and workers alike were sent out into the surrounding villages and farms, instructed to beg or barter for whatever they could. They organised foraging lessons for the hospital community and worked out how to subvert the rationing system. ‘There were special ration cards for TB patients,’ said Tosquelles, so ‘when a guy showed signs of malnutrition, we’d immediately diagnose him with tuberculosis’.

The hospital was simultaneously housing vulnerable patients and hiding armed paramilitaries

So confident was Tosquelles, so resolute, that the hospital soon started taking in even more mouths to feed. Jews fleeing persecution were welcomed and cared for, and not only by the staff. ‘Some of the patients began helping the refugees, feeding them and so on,’ Tosquelles said later.

In 1943, Balvet left for another hospital and was replaced by Lucien Bonnafé, a communist, resistance fighter and self-described ‘outlaw’. Moving to Saint-Alban to escape the Nazis, he brought his militant contacts with him. Together, he and Tosquelles turned the hospital into a shelter for members of the Francs-Tireurs et Partisans, the armed wing of the French Communist Party who were sabotaging Nazi operations in the region.

This part of the story provokes in me a prickle of alarm and dissonance: the hospital was simultaneously housing vulnerable patients and hiding armed paramilitaries, bringing the high risk of violence into what was meant to be a safe haven. But Tosquelles drew a direct equivalence between the political and the psychiatric activities at Saint-Alban; after all, the patients were aware of the war and knew that the castle sheltered resistance fighters:

They were hidden like them. The word ‘asylum’ is very good … ‘Asylum’ means that someone can take refuge there or that they are forced to take refuge there.

When I reflect on what unsettles me about this vision of the ‘asylum’, housing both patients and dissidents, I am aware that the fear is rooted in my understanding of what those words mean. ‘Patient’ means vulnerable, sick, incapable. ‘Dissident’ means violent, strong, dangerous. But what Tosquelles and Bonnafé were able to see was that neither of these roles was fixed – patients could be strong, dissidents could be vulnerable. Moreover, both groups were engaged in the common project of resisting fascism. However militant this work might become, it was justified by reference to the much greater violence it opposed. Ordinary ethical boundaries, Tosquelles and Bonnafé knew, could not be applied.

It was only the ‘debacle’ of the war, Tosquelles said, that allowed for the ‘awakening’ of Saint-Alban. ‘It was the Resistance which, beyond the diversity imposed by the patients, created the variety of the entourage,’ he said. In Bonnafé’s terms, the Nazi occupation shifted ‘the I towards the Us’.

It’s this mutualism – this inclusive vision of antifascist practice, the ability to imagine patients not as passive objects but as agents in their own destiny – that marked the difference between Saint-Alban and the other asylums in France, where so many people died.

The factors leading to the starvations across France were not only practical but psychic: there were limitations on what it was possible to think.

When Balvet left Saint-Alban in 1943, he took up a post at France’s second-largest hospital, the Vinatier near Lyon, where more than 2,000 patients died during the war. Years later, when asked by one interviewer why he and his colleagues didn’t send patients home to their families when it became clear that they were starving, he said: ‘It would not have occurred to anyone.’

This is an example of what the historian Camille Robcis calls ‘psychic occupation’: the constraining effect of France’s own culture on the minds of its population even before the territorial occupation began. This took the form of shared beliefs and assumptions, but was also enforced through government policy: it was what the writer James Baldwin called a ‘system of reality’.

Under the laws that governed asylums before the war, families were required to pay fees unless the person being committed was declared dangerous and placed under compulsory care. Unsurprisingly, 90 per cent of patients fell into this category, with the legal status of prisoners. For clinicians under the occupation, whose patients were dying from hunger, this presented an ethical quandary and a personal dilemma. To release a patient deemed ‘dangerous’ was irresponsible and possibly immoral; it was also an offence that might get a doctor stripped of the right to practise.

Even with the arrival of ‘scientific’ psychiatry, patients were routinely imprisoned, tortured and starved to death

There was an earlier situation, at Saint-Alban, in which Balvet also needed help to ‘disoccupy’ his attitudes. In order to justify housing Jewish refugees, he was required to disguise them as patients by diagnosing them with an illness. ‘I probably had scruples,’ he said later. ‘[I thought] it was unethical.’ It didn’t take long for him to be persuaded, but the struggle reveals the fixity of the mindset he had to overcome.

The distinction here is between the psychiatrist as a warden of the establishment and the psychiatrist as an instrument of change. If a doctor has internalised a system of reality in which the status quo is just and proper, and in which a ‘doctor’ is a person who upholds the status quo, they’re unlikely to react effectively when that status quo aligns itself with an international death cult. Under these circumstances, as Tosquelles put it: ‘A good citizen is incapable of doing psychiatry.’

The construction of the role of ‘patient’ also contributed to the disaster. By the time the war broke out, madness in Europe had long been synonymous with suffering and death. In the Middle Ages, people experiencing what would now be called psychosis were liable to be cast out or tortured as the victims of demonic possession. Even with the arrival of supposedly ‘scientific’ psychiatry in the 19th century, patients were routinely imprisoned, tortured and starved to death. By 1900, the science of eugenics was common currency in both Europe and the United States, with medical authorities recommending the mass murder of the ‘feeble-minded’ and the ‘insane’ as a means of protecting the species from decline.

In France, the symptoms of this legacy were in plain evidence at the outbreak of the Second World War. France had 96 psychiatric hospitals in operation. Collectively, they had a capacity of 85,000 but were housing more than 110,000 patients, with just 200 psychiatrists employed in their care – a ratio of one doctor to every 550 patients.

After decades of underfunding, defeatism had set in among the profession. The inertia of the authorities ‘reduced the doctors to a disastrous impotence, the sick to an existence which destroyed any chance of recovery,’ as one psychiatrist put it in 1952. Another recalled in 1979 that there was always an ‘indifference’ to psychiatric patients. ‘People didn’t care.’

What Tosquelles tacitly acknowledged, when he referred to the patients feeding refugees, was that they too played a role in the development of Saint-Alban’s antifascist practice. Patients helped clean, cook and run the hospital’s farm. They worked on its internal newspaper, which featured articles describing the lives of patients, critiquing the canteen, and examining the purpose of psychiatry. Meetings were held almost continually, with everyone invited, and any activity could be the occasion for debate. As Tosquelles later explained: ‘Nothing should ever be obvious, and everything is subject to discussion.’

This is all visible in the filmmaker Martine Deyres’s documentary Our Lucky Hours (2019), which captures life at the hospital during and after the war. We see people dancing, strolling in the hospital’s gardens, playing pool and cards, smoking and socialising. We see them earning a living in the hospital’s ergotherapy workshops: doing carpentry and metal work, running the printing press, mending shoes, all with evident skill and confidence.

If you didn’t know what you were looking at, it would be hard to tell that the people in the film are patients at all, given their everyday attire. A picture taken during a hiking expedition shows the children of the staff nestling in the laps of patients. ‘Nobody feared the patients,’ says a former nurse. ‘I never put a patient in a straightjacket.’ Another employee explains how his children would roam from ward to ward, visiting patients, and how patients were free to leave. ‘The tavern would phone us,’ he says, ‘“Please come pick up So-and-So because he’s had too much to drink.” Two nurses would go and fetch the patient. We thought nothing of it.’ In order to bring the hospital closer to the village around it, the perimeter wall separating the two was torn down.

Psychiatry, as previously conceived, too closely mirrored the mentality of occupation

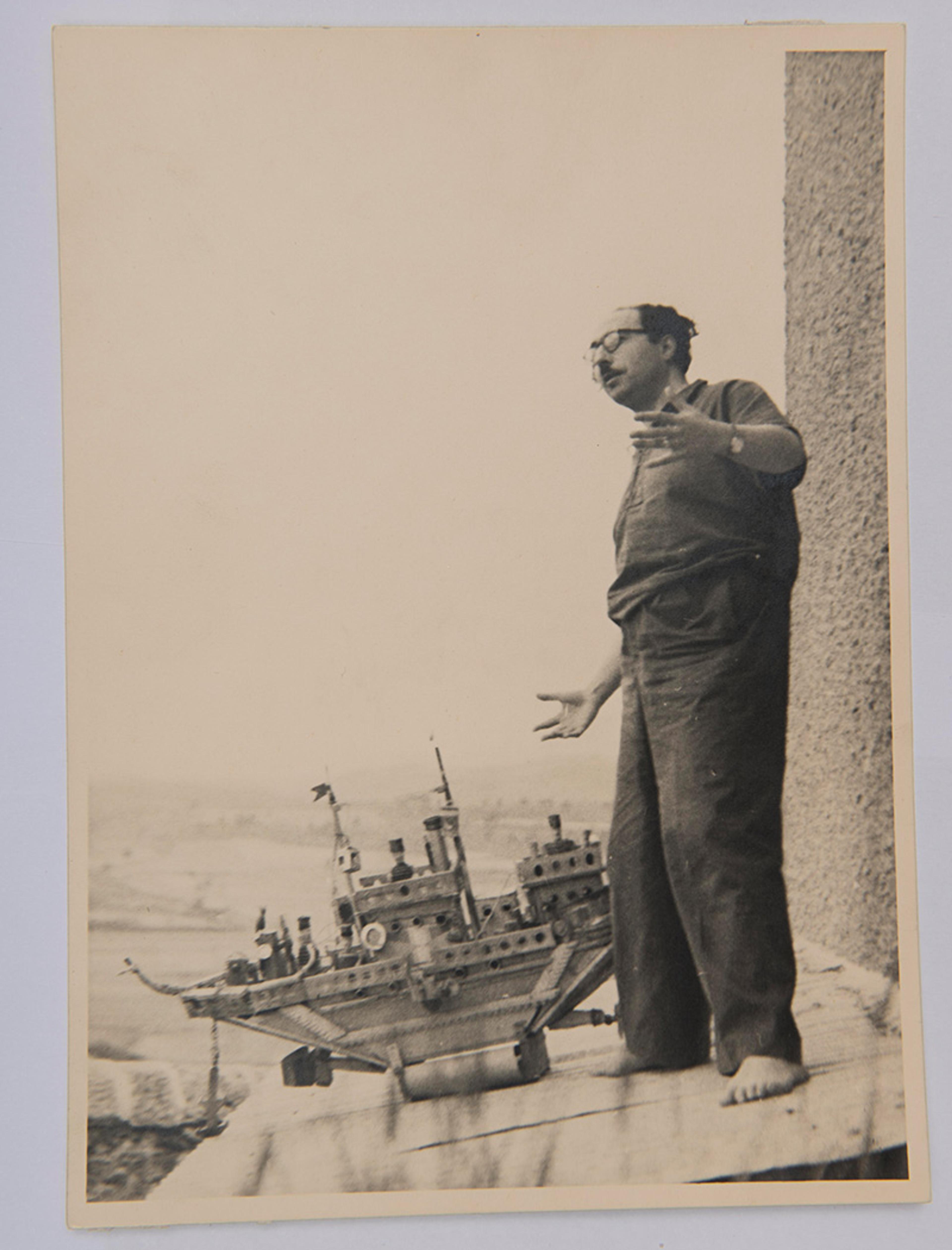

While early photographs show the doctors wearing the white coats of their trade, hospital policy soon changed to reject uniforms. In later images, they wear rather shabby jackets – or, as in one striking image, we see Tosquelles bare-footed, wild-haired, standing on part of the hospital’s roof, holding an impressive model boat above his head. When I first saw it, I assumed the person featured was one of the patients – perhaps the maker of the boat. He couldn’t look less like the archetype of a psychiatrist. In allowing himself to be photographed in this way, Tosquelles exploded the distinction between himself and ‘les fous’ with whom he lived and worked.

François Tosquelles on the roof at Saint-Alban. Photo by Roman Vigouroux and courtesy the Archives of the Tosquelles Family

The policy of integration – between staff and patients, hospital and community – was by no means merely aesthetic or conceptual. It was driven by the conviction that there was something fundamentally wrong with psychiatry as previously conceived, that it too closely mirrored the mentality of occupation, of colonialism, of the ‘concentrationism’ of territorial wars: impulses that were rooted more in the desire for containment and control than in the search for human wellbeing. Seeing that the hospital itself was ‘sick’, the leadership decided the solution was, as Tosquelles put it, ‘to make the patients and the staff work to cure the institution’.

At Saint-Alban, the ‘institution’ became a place of collaboration and of mutual benefit for patients and staff alike. ‘People call them “lunatics” but not me,’ as one former employee puts it in Our Lucky Hours. ‘We owe everything we have to the hospital. To Saint-Alban.’

The maker of the boat that Tosquelles was holding was Auguste Forestier, one of several artists in residence at Saint-Alban. His story illustrates both the patients’ influence on the way of life at the hospital and the interplay that emerged there between antifascism and creativity.

From a young age, Forestier had all of the defining predispositions of an artist: acute engagement with the present, the need to experiment, and an absolute dependence upon freedom. Captivated by the railway, as an adolescent he began taking unpaid trips to wherever the train would carry him – Clermont-Ferrand, Nevers, Toulouse – from where the police would inevitably return him, protesting, to his parents.

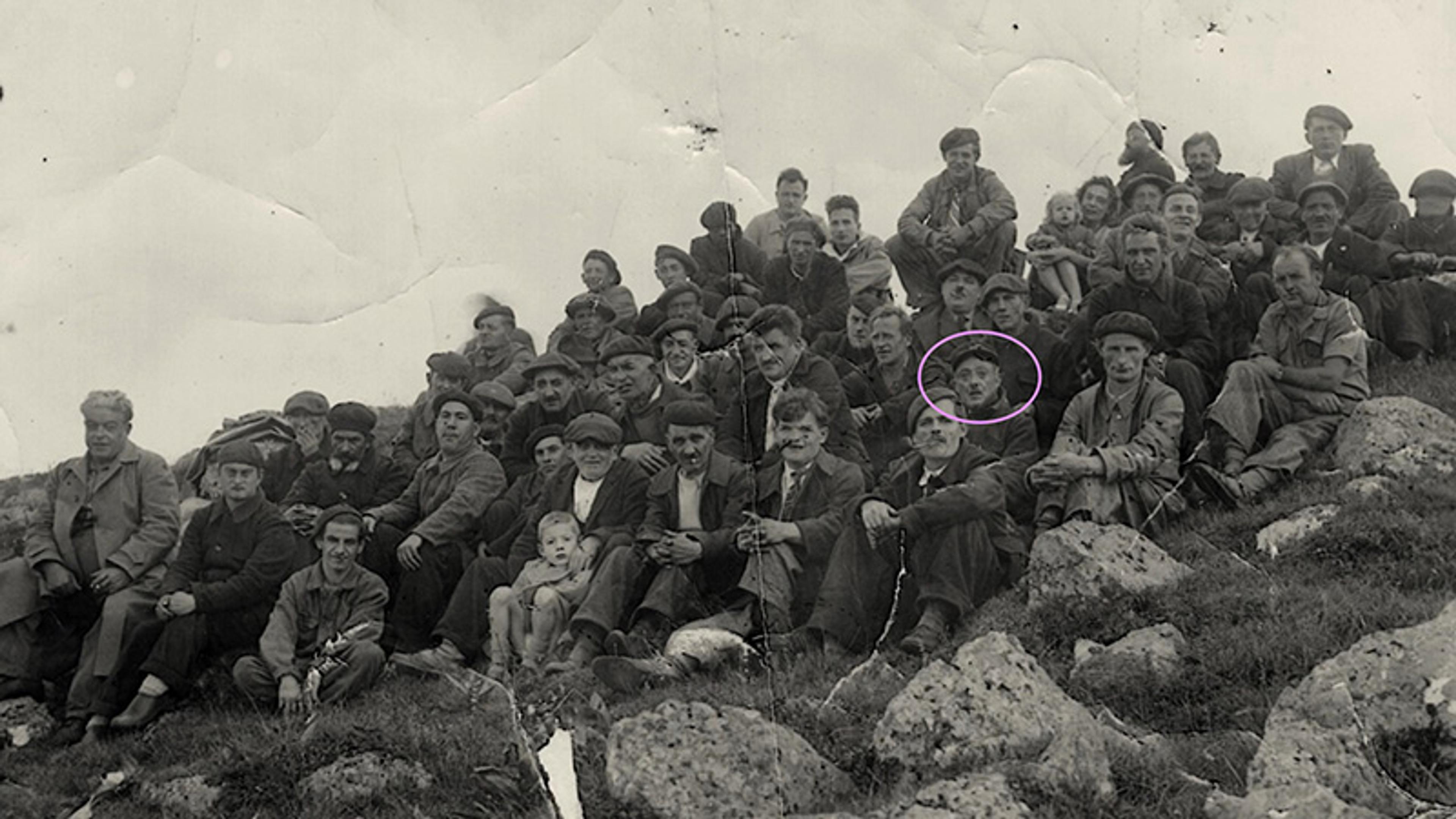

A group of patients from Saint-Alban, c1952; Auguste Forestier is circled. Photo courtesy Yves Baldran

He was committed to Saint-Alban in 1914, at the age of 27, after causing a derailment by piling rocks on the line in the hope of seeing the train crush them. (While held in prison, he is said to have carved some wooden medals for himself, claiming they had been given to him by the railway company in recognition of his good works.) He didn’t go entirely quietly, making five escapes between 1914 and 1923, but during this time he also began to further develop the imaginative aspects of his roaming practice. He pored over magazines and history books in the hospital’s library, taking inspiration for many drawings, a number of which were collected by the then-director Maxime Dubuisson, who took them home in a scrapbook, which he shared with his grandson – a young Lucien Bonnafé.

Bonnafé explained later that it was seeing this work as a child, along with that of other patients, collected by his grandfather, that taught him ‘not to treat the creations of madmen, with whom my life has been strewn, as objects of a pathological gaze’.

By the time that Bonnafé arrived at Saint-Alban as an adult, Forestier had moved on to carving and assemblage, combining wood, bones and other materials gleaned from the hospital into extraordinary sculptures, exploring his passions for military and naval regalia, animal life, mythology and machines. Recognising the importance of his practice, Bonnafé and Tosquelles encouraged Forestier to set up a workshop in an alcove next to the kitchen, a place where he could remain central to the life of the community while not being disturbed.

Paul Éluard admired the kind of artist who ‘refuses to serve an absurd order based upon inequality’

Jean Oury, a psychiatrist who interned at Saint-Alban after the war, later described the way that Forestier was protected. ‘Everyone was very attentive, making sure he had his tools and could work in peace.’ Forestier, he said, was in ‘a permanent struggle against shattering and destruction. He reconstructed the world constantly.’

Another Saint-Alban resident who understood the alignment of antifascism, psychiatry and creativity was the poet Paul Éluard. He was forced into hiding during the war when the British air-dropped thousands of copies of his poem ‘Liberté’ across France, by way of encouraging the resistance. Sheltering at Saint-Alban during the winter of 1943-44, he supported patients on the wards, helped with the publication of pamphlets for the resistance, and participated in the endless meetings that were the centre of the hospital’s life at the time. He also bought several of Forestier’s sculptures. (Among those who later saw the sculptures at Éluard’s home were the writer Raymond Queneau and the painter Pablo Picasso, both of whom were moved to acquire some of their own. The painter and sculptor Jean Dubuffet also saw and was intrigued by Forestier’s work, and soon began his collection of what he came to call ‘Art Brut’.)

Untitled (1935-49) by Auguste Forestier. Photo by Claude Bornand, Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne

We don’t know exactly what drew Éluard to Forestier because he never wrote about it explicitly – but there are clues in his archive. In a lecture in 1936, he gave a description of the kind of artist he admired. ‘The unprecedented is familiar to them,’ he said, ‘premeditation unknown.’ Such artists, he said, were aware of the temporary, ‘fugitive’ nature of the relationships between things, and were driven by a desire to liberate themselves from the separation of imagination and reality, to cancel the dualism of spirit and flesh.

The lecture was given several years before Éluard visited Saint-Alban and the artists he was referring to were in fact the surrealists, such as his friend Max Ernst. But I think the description could just as easily apply to Forestier, in whose work I believe Éluard discerned precisely this combination of liberty and unity. I suspect he also saw a glimmer of some wider agenda, the one to which he dedicated the surrealist movement: that which ‘refuses to serve an absurd order based upon inequality,’ and which seeks ‘the total emancipation of humanity’.

The concentration of distressed and disabled people in secure institutions isn’t as fashionable now as it once was, but the system of reality that promotes indifference to their fate is alive and well. It can be seen in a news media that gives a platform to people who say things like: ‘Two-thirds of coronavirus fatalities would have probably died within the year anyway.’ It surfaces when the murders of disabled people by their carers are presented as ‘mercy killings’. And it is called upon when lawyers claim that a man lying on the ground with the knee of a police officer crushing his airway died of ‘underlying health conditions’.

Plenty of readers will feel uneasy at the suggestion that this system of reality, the one that prevails in Europe and the US today, might be referred to as ‘fascism’. As I once did, many will prefer to think of fascism in the terms used by some historians, as something defeated 80 years ago in Europe and that’s since been in abeyance, aside from the behaviour of a few deranged marginals. Others might understand fascism as a persisting threat, but view it as a distinct component of the political spectrum, promoted mostly by the white supremacists and ethno-nationalists we’ve heard so much from in the past decade.

But the idea that fascism should be viewed as something wider and more insidious – something that’s in here as well as out there – has a long history. In her essay from 1940 on Homer’s Iliad, Simone Weil noted the ‘indifference’ of the strong towards the weak, and reflected on the use of force throughout human history: ‘Exercised to the limit, it turns man into a thing in the most literal sense: it makes a corpse out of him’ while he is still alive. In the wake of the war, Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno were clear that fascism had found continuity in the combination of bureaucracy and capitalism that dominated the postwar world, a political system that ‘relieves its peoples of the burden of moral feelings’, and ‘deeply in accord with pure reason … treats human beings as things’.

The antidote to this day-to-day fascism is not military but intellectual, emotional and communal

This is also what Michel Foucault was referring to in 1977 when he wrote about ‘the fascism in us all, in our heads and in our everyday behaviour, the fascism that causes us to love power, to desire the very thing that dominates and exploits us’.

Today, the journalist Natasha Lennard says ‘we can and should apply a more capacious understanding of fascism than simply, “How much like Mussolini’s Italy or Hitler’s Germany is this?”’ We should use the word, she says, ‘to describe a set of tendencies, desires, habits, and collective practices’ that can thrive even in regimes that seem to be democratic. The antidote to this day-to-day fascism, says Lennard, is not military but intellectual, emotional and communal.

Neither the Nazis nor their Vichy counterparts needed to exert themselves in causing the deaths of 45,000 psychiatric patients in France. It was easy because the French population had already assented to a culture of indifference towards these people, had turned them into expendable ‘things’, into corpses waiting to be killed. It is this same indifference that explains why the deaths remained largely unacknowledged outside clinical circles for 40 years after the war ended. It is this same indifference, left unchecked, that we turn on ourselves today, that we marshal in order to participate in lives governed by powers beyond our influence, by defeatism, by injustices we accept as inevitable.

Saint-Alban’s legacy seems uncertain. The principles of localism and community provision that it promoted were formalised across France in the 1960s as ‘sector psychiatry’. Oury, the intern, went on to set up a clinic in its image at La Borde in the Loire Valley, which is still in operation.

But when the historian Robcis met with Oury in 2013, the year before his death, he described his fear that the ‘project would end with him’. Saint-Alban, now known as the François Tosquelles Hospital Centre, continues to offer psychiatric services but has moved steadily towards what Oury called ‘technocratic simplism’, a dehumanising culture of ‘bureaucratic requirements and administrative measures developed under the mask of pseudoscientific progress’.

The Saint-Alban of the 1940s might no longer exist but its message is there for those that want to hear it. First, it reminds us to stay vigilant about which people we are making vulnerable, a lesson whose relevance has not diminished. Second, it tells us to remain open-minded about institutions. Too often they have been used as dumping grounds for unwanted people. The decommissioning of psychiatric hospitals in Britain and the US during the Reagan/Thatcher era was sold to the public on the basis that such places were inhumane, which many of them were. But, equally, an institution’s function is led by its intentions. The post office is an institution. So are universities and food cooperatives. Nothing mandates that psychiatric hospitals must imprison, isolate and mistreat the people that use them. Saint-Alban shows us that they can be places of hope, of bridge-building, and of flourishing creativity.

Antifascism can’t be delivered as a service. Liberation works only if it includes everyone as actors

Saint-Alban also represents a real-world demonstration of the communal, affective, day-to-day antifascist practice that Lennard says we now need. At Saint-Alban, every part of daily life was an opportunity for resistance, for the members of its community to examine and soften their own and each other’s fascist impulses. A true ‘asylum’, it recruited not just the unusual and unwanted to this project – those like Forestier – but also the townspeople who worked there, Jewish refugees, artists and intellectuals, and the psychiatrists themselves. It supported everyone to flourish. Nobody was undeserving of protection and no one was exempt from the work of liberation.

Lastly, and perhaps most importantly, Saint-Alban shows us that antifascism can’t be delivered as a service, or applied to one group in isolation by another. Vulnerable people can’t be emancipated passively, as some kind of special measure, by dispassionate professionals. No matter what first motivates it, liberation works only if it includes everyone as actors, every day.

We are all subject, to a greater or lesser extent, to the deadening, separating effects of day-to-day fascism: in our workplace hierarchies, our state bureaucracies, our interactions with strangers, even our friends. But Saint-Alban shows us that this is neither necessary nor inevitable. If they could bring antifascism to life at a medieval castle in rural southern France under occupation, then what’s stopping us here and now? If we have the courage to try, it’s never too late to set ourselves – and each other – free.

The film Our Lucky Hours is available online here. You can read and listen to a conversation between Ben Platts-Mills, the film’s director Martine Deyres and the historian Camille Robcis here.

To read more on the history of psychiatry, visit Psyche, a digital magazine from Aeon that illuminates the human condition through psychology, philosophy and the arts.