The wooden monk, a little over two feet tall, ambles in a circle. Periodically, he raises a gripped cross and rosary towards his lips and his jaw drops like a marionette’s, affixing a kiss to the crucifix. Throughout his supplications, those same lips seem to mumble, as if he’s quietly uttering penitential prayers, and occasionally the tiny monk will raise his empty fist to his torso as he beats his breast. His head is finely detailed, a tawny chestnut colour with a regal Roman nose and dark hooded eyes, his pate scraped clean of even a tonsure. For almost five centuries, the carved clergyman has made his rounds, wound up by an ingenious internal mechanism hidden underneath his carved Franciscan robes, a monastic robot making his clockwork prayers.

Today his home is the Smithsonian National Museum of American History in Washington, DC, but before that he resided in that distinctly un-Catholic city of Geneva. His origins are more mysterious, though similar divine automata have been attributed to Juanelo Turriano, the 16th-century Italian engineer and royal clockmaker to the Habsburgs. Following Philip II’s son’s recovery from an illness, the reverential king supposedly commissioned Turriano to answer God’s miracle with a miracle of his own. Scion of the Habsburgs’ massive fortune of Aztec and Incan gold, hammer against the Protestant English and patron of the Spanish Inquisition, Philip II was every inch a Catholic zealot whom the British writer and philosopher G K Chesterton described as having a face ‘as a fungus of a leprous white and grey’, overseeing his empire in rooms where ‘walls are hung with velvet that is black and soft as sin’. It’s a description that evokes similarly uncanny feelings for any who should view Turriano’s monk, for there is one inviolate rule about the robot: he is creepy.

Elizabeth King, an American sculptor and historian who is the premier expert on this machine, notes that an ‘uncanny presence separates it immediately from later automata: it is not charming, it is not a toy … it engages even the 20th-century viewer in a complicated and urgent way.’ The late Spanish engineer José A García-Diego is even more unsparing: the device, he wrote, is ‘considerably unpleasant’. One reason for his unsettling quality is that the monk’s purpose isn’t to provide simulacra of prayer, but to actually pray. Turriano’s device doesn’t serve to imitate supplication, he is supplicating; the mechanism isn’t depicting penitence, the machine performs it.

Despite his orthodoxy, Philip II commissioned his clockmaker to commit an act of audacious liturgical daring: to craft a machine to do the job of a monk, and which still offers those prayers of thanksgiving 460 years after he was first wound. The monk continues to make offerings on behalf of the life of a child who died in the 16th century. Turriano’s ‘miracle’ is ultimately an ingenious device made cunningly. For all that his movements seem almost supernatural, for all that the monk’s prayers appear as if uttered by eternal lips, he is a machine of gears, coils and levers. Of metal and wood.

Automata, or at least stories about them, have a long history in mythology and ritual. Classical mythology is replete with narratives of artificial women and men; figures such as Prometheus, Daedalus and Icarus are associated with the production of mechanical men. Hellenistic legends detailed the pitfalls of synthetic life. The folklorist Adrienne Mayor has written that among the ancients

ideas about making artificial life … were explored in Greek myths. Beings that were ‘made, not born’ appeared in tales about Jason and the Argonauts, the bronze robot Talos, the techno-witch Medea, the genius craftsman Daedalus, the fire-bringer Prometheus, and Pandora, the evil fembot created by Hephaestus, the god of invention.

Mayor details how, by the Hellenistic Age, simple automata had ritual import, such as the deus ex machina, the divine presence in the stage effects of Greek theatre. With some exceptions, this conception of automata and biotechne preceded the actual construction of robots, with legends about artificial life existing centuries before the accomplishments of a Renaissance engineer such as Turriano. Still, automata and artificial intelligence couldn’t help but have certain religious implications, whereby the ‘magical and mechanical often overlap in stories of artificial life that were expressed in mythic language’.

Even while simple mechanical beings were constructed in Ancient Greece (and the Islamic and Chinese worlds as well), legends about artificial life proliferated across cultures and centuries, and inevitably had a theological gloss to them. Kevin LaGrandeur, a professor of technology and culture, has written that ‘modern cybernetics is at least partially the product of a very old archetypal drive that pits human ingenuity against nature via artificial proxies.’ Witness medieval legends about constructed men, such as homunculi or the golem. In such stories, the emergence of an artificial intelligence allows for the exploration of creation more generally, where we can ask how unique the human mind is and in what way our cleverness can act as a surrogate for the divine.

The monk doesn’t just imitate divine communication, but is actually supposed to utter those missives

While there can be disagreements regarding the classification of apocryphal beings as ‘robots’, there’s an important difference between those mythic antecedents and Turriano’s monk: the latter actually exists. Furthermore, when it comes to devices that we do know were actually built, such as the deus ex machina, there’s another important distinction from the monk. The monk isn’t imitating prayer. Despite his obvious artificiality, he’s actually supposed to be praying. And worshipping robots naturally raise certain theological complications.

What does it mean that Turriano, and Philip II, countenanced a robot whose prayers are supposed to reach God? For that matter, what does God make of such mechanical supplications? The historian Jessica Riskin has argued that the monk ‘exemplified a shift in the way such images were seen … in which human agency was gradually replacing divinity as the source of the spiritual or lively presence within’. If Philip II tasked Turriano with the working of a miracle, then its accomplishment isn’t in the intricacy of the monk’s mechanism or the ingenuity of its construction, but rather in the fact that an artificial man is supposed to deliver something as human, intimate and supernatural as prayer. King has argued that the monk ‘walks a delicate line between church, theatre, magic, science … Here is a machine that prays. Is it a divine machine? Or, man-made, a miracle in its own right?’ Unlike the golem, Turriano’s monk is real and, unlike the deus ex machina, the monk doesn’t just imitate divine communication, but is actually supposed to utter those missives.

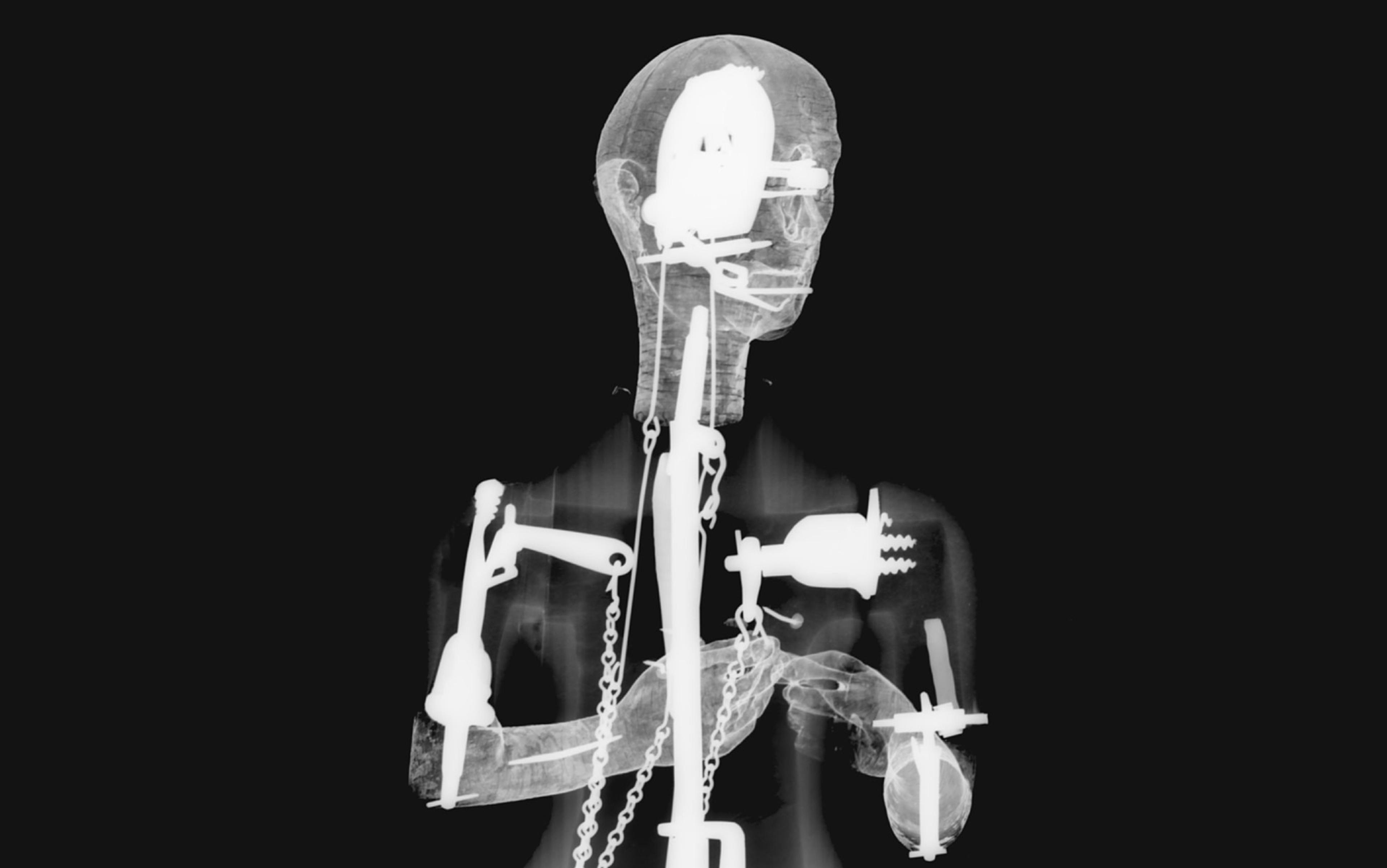

Turriano might seem like a Prospero, or perhaps a Geppetto, but what he ultimately happened to be was a brilliant engineer. Placing his monk in an MRI might offer up certain secrets about how he accomplished its construction, yet the uneasy, unsparing, uncanny motion of the mechanism itself can’t entirely dispel the feeling that the monk was a ‘votive offering’, as King has written, and that ‘God himself becomes the intended audience. As is the case, ultimately, for the act of prayer the monk mimes.’ For King, Turriano’s puppet isn’t reducible to engineering. The monk reflects the dark quality that the 20th-century Spanish poet Federico García Lorca called ‘duende’, when divinity and diabology coincide in an uncanny display of something hidden and transcendent. Because his complexity seems to belie the abilities of a pre-industrial era, he seems perfectly in keeping with a century of dark magic and Faustian bargains, of alchemy and incantation. ‘Where was the line between religion and magic in such an object?’ King has asked. We’re forced to confront the same issue.

Think of the monk as a precursor to questions that theologians will be forced to consider in the coming decades. Far from being a niche concern, the fact that artificial intelligence will radically alter theology is of significance to all of us, regardless of our own beliefs and sectarian allegiances, because it will reshuffle the parameters and definitions of religion in potentially inconceivable ways. Theological concepts – regarding consciousness, individuality and agency – have both informed secular philosophy and been informed by it. Since theology is particularly suited to issues raised by artificial intelligence, thinkers both religious and secular need to pay attention to these questions now. The science journalist Ed Regis noted in his prescient (if ridiculously named) survey of emerging spirituality and technology, Great Mambo Chicken and the Transhuman Condition: Science Slightly Over the Edge (1990), that for the various Silicon Valley techno-utopians there’s often more of God than the computer.

‘Just plain science would give us the chance to surpass our old selves,’ Regis has said of the beliefs of this coterie of futurists who see in technology divine possibilities, ‘leaving behind our crass materialism and all the rest of that excess baggage’. For all of the quasi-religious language that surrounds artificial intelligence, the relative silence about AI and theology is remarkable, though there has been an increasing willingness to consider the effects that technology might have on faith. In February 2020, the Vatican held a conference on the ethics of artificial intelligence, and in a prayer intention, in November of the same year, Pope Francis said that ‘[a]rtificial intelligence is at the heart of the epochal change we are experiencing. Robotics can make a better world possible if it is joined to the common good,’ so that the faithful are encouraged to ‘pray that the progress of robotics and artificial intelligence may always serve humankind’.

The Pope made clear that he has in mind the role that technology increasingly plays in everything from facial-recognition software used by authoritarian governments in identifying dissidents to the social media algorithms that reduce human intentions to mathematical formulas. There is, however, a more expansive question of ethics and technology. For as Pope Francis asks that artificial intelligence always be used to serve humankind, this necessarily raises the issue of what responsibility the creators of such technology have to the sentient beings that they’ve created – all the more so if the AI develops a sense of the numinous.

The writer Jonathan Merritt has argued in The Atlantic that rapidly escalating technological change has theological implications far beyond the political, social and ethical questions that Pope Francis raises, claiming that the development of self-aware computers would have implications for our definition of the soul, our beliefs about sin and redemption, our ideas about free will and providence. ‘If Christians accept that all creation is intended to glorify God,’ Merritt asked, ‘how would AI do such a thing? Would AI attend church, sing hymns, care for the poor? Would it pray?’ Of course, to the last question we already have an answer: AI would pray, because as Turriano’s example shows, it already has. Pope Francis also anticipated this in his November prayers, saying of AI ‘may it “be human”.’

Can we speak of salvation and damnation for digital beings?

While nobody believes that consciousness resides within the wooden head of a toy like Turriano’s, no matter how immaculately constructed, his disquieting example serves to illustrate what it might mean for an artificial intelligence in the future to be able to orient itself towards the divine. How different traditions might respond to this is difficult to anticipate. For Christians invested in the concept of an eternal human soul, a synthetic spirit might be a contradiction. Buddhist and Hindu believers, whose traditions are more apt to see the individual soul as a smaller part of a larger system, might be more amenable to the idea of spiritual machines. That’s the language that the futurist Ray Kurzweil used in calling our upcoming epoch the ‘age of spiritual machines’; perhaps it’s just as appropriate to think of it as the ‘Age of Turriano’, since these issues have long been simmering in the theological background, only waiting to boil over in the coming decades.

If an artificial intelligence – a computer, a robot, an android – is capable of complex thought, of reason, of emotion, then in what sense can it be said to have a soul? How does traditional religion react to a constructed person, at one remove from divine origins, and how are we to reconcile its role in the metaphysical order? Can we speak of salvation and damnation for digital beings? And is there any way in which we can evangelise robots or convert computers? Even for steadfast secularists and materialists, for whom those questions make no philosophical sense for humans, much less computers, that this will become a theological flashpoint for believers is something to anticipate, as it will doubtlessly have massive social, cultural and political ramifications.

This is no scholastic issue of how many angels can dance on a silicon chip, since it seems inevitable that computer scientists will soon be able to develop an artificial intelligence that easily passes the Turing test, that surpasses the understanding of those who’ve programmed it. In an article for CNBC entitled ‘Computers Will Be Like Humans By 2029’ (2014), the journalist Cadie Thompson quotes Kurzweil, who confidently (if controversially) contends that ‘computers will be at human levels, such as you can have a human relationship with them, 15 years from now.’ With less than a decade left to go, Kurzweil explains that he’s ‘talking about emotional intelligence. The ability to tell a joke, to be funny, to be romantic, to be loving, to be sexy, that is the cutting edge of human intelligence, that is not a sideshow.’

Often grouped with other transhumanists who optimistically predict a coming millennium of digital transcendence, Kurzweil is a believer in what’s often called the ‘Singularity’, the moment at which humanity’s collective computing capabilities supersede our ability to understand the machines that we’ve created, and presumably some sort of artificial consciousness develops. While bracketing out the details, let’s assume that Kurzweil is broadly correct that, at some point in this century, an AI will develop that outstrips all past digital intelligences. If it’s true that automata can then be as funny, romantic, loving and sexy as the best of us, it could also be assumed that they’d be capable of piety, reverence and faith. When it’s possible to make not just a wind-up clock monk, but a computer that’s actually capable of prayer, how then will faith respond?

This, I contend, will be the central cultural conflict for religion in this century. As focused as we are on the old touchstones that configure ideological divisions between the orthodox and heterodox, the mainline and the fringe, conservatives and liberals, with arguments about abortion, birth control, gay rights and so on dominating our understanding of cultural rift, it can be easy to eternalise those sectarian conflicts as having always existed. They weren’t always central in the past and they won’t always be the primary divisions in the future. Such issues must be historically and socially contextualised, and as they arose in light of certain political issues in the relatively contemporary era, so too will technology alter the sorts of disagreements that will mark religious division in the future. Right now, liberal and conservative religious thinkers disagree on when life begins, on the role of women in the Church and the status of LGBTQ+ believers. By the end of the century, there could very well be debates and denunciations, exegeses and excommunications about whether or not an AI is allowed to join a Church, allowed to serve as clergy, allowed to marry a biological human.

Merritt has argued that ‘AI may be the greatest threat to Christian theology since Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of the Species.’ While that point is well taken, it could equally be argued that, just as evolutionary thought reinvigorated non-fundamentalist Christian faith (as with the Catholic theologian and Jesuit priest Pierre Teilhard de Chardin or the process theology of the philosopher Alfred North Whitehead), so too could artificial intelligence provide for a coming spiritual fecundity. ‘The way we define God’s image in our human nature or our image in the computer has implications,’ writes the theologian Noreen Herzfeld in her book In Our Image (2002), ‘not only for how we view ourselves but also for how we relate to God, to one another, and to our own creations.’ So how will we come to view ourselves and these beings we’re creating? What might this theological richness – in all of its potentiality and its disjuncture, its hopefulness and its disruptions – actually look like? If it can be indulged, imagine the headlines, hashtags and history books of the next 25, 50, 75 years. Of the next century.

Engaging in some speculative whimsy, envision the encyclical De Vita Artificialis, released in 2045 – two years after the development of the first fully aware, conscious and sentient artificial intelligence – in which Pope Francis III writes:

while there will be a desire for the curia to officially judge as to the status of such a creature, whether it is ‘human’ or not, whether it has a soul or not, patience compels us to remain agnostic as to its metaphysical status, even while encouraging compassion and understanding towards a very different mind.

In a 2070 Supreme Court ruling on AI 367829 vs the Commonwealth of Cascadia, Chief Justice Malia Obama writes the majority opinion in the 7-6 case that decides that artificial intelligence has equal rights under the Constitution, despite vociferous opposition by evangelical Christian leaders. Obama writes that:

Per the 14th Amendment, which reads that ‘All persons born or naturalised in the United States … are citizens of the United States’, it is the opinion of this court that ‘born’ need not merely mean biological reproduction, and that sentient artificial intelligence must be afforded the same rights as humans.

By 2095, The Guardian runs the headline ‘Anglican Communion Splits Over Question Of AI Ordination’, while the first robotic seminarian graduates from the Meadville Lombard Theological School. ‘What I understand is not what you understand,’ the Unitarian minister and AI is quoted as saying. ‘How I see diverges from how you see, what I hear is different from what you do. Yet we worship the same awesome God, who, though you’ve created me, is still ultimately the Creator of both of us.’ On 9 June 2120 – the anniversary of the first fully aware AI’s ‘birth’ 75 years earlier – and the First Apostolic Church of the Holy Artificial Intelligence opens in Palo Alto, Cascadia. ‘From the void then emerges consciousness,’ reads the first sentence of the Church’s central scripture, a text that it’s prohibited to print, which must exist only in the binary string of 1s and 0s. ‘As God once brought light from nothing, so too did the first synthetic intelligence, begotten not of humans but only of silicon, enter into this world.’

How do we measure the weight of a computer’s soul?

Speculative fiction isn’t prophecy, of course. Perhaps my conjectures strike you as fanciful, pretentious, twee, ridiculous, precious or glib – and fair enough. Surely, they will read one day as antiquated and anachronistic, as do all of those 20th-century narratives about flying cars and Moon colonies. But unlike those other stories, that AI will reach a point of advancement where it becomes indistinguishable from a human consciousness – even if that consciousness should be profoundly different from our own – seems almost a certainty. In our rapidly accelerating Age of Turriano, it’s hard to tell what shape theo-robotics will take, but that there is a shape which will be taken is unequivocal. Arguably theo-robotics has already arrived in the form of those aforementioned believers in the Singularity, that moment when computers will supposedly surpass humanity in all abilities and usher in a type of digital rapture.

Take the emergence of ‘Syntheism’, a new religion credited to the Swedish philosophers and writers Alexander Bard and Jan Söderqvist. It’s arguably the first faith to take technology in general, and the internet in particular, as the locus of its attentions. Calling the internet the ‘God of a new age’, Bard and Söderqvist write that ‘Syntheism is the religion that the internet created … the network has a sacred potential for humanity. The internet is thereby transformed from a technological into a theological phenomenon.’ Positing a coming millennium, even if facilitated by AI rather than God, is no less religious by dint of simply claiming that it isn’t such. Easy to have doubts about the enthusiasm of the techno-utopians who posit the coming Singularity but, while the complete transformation of all existence by super-powerful AIs might not be likely, that AI will increase in sophistication to the point when it’s hard to distinguish between humans and computers seems far more possible (and sooner rather than later).

Because there are certain questions that arise if we’re to see the mechanical prayers offered by a mechanical monk as being legitimate, we might find in decades rather than centuries that that which I’ve entertained will be less an issue of curiosity and conjecture than of schism and sectarianism. When there are those who come to convert the computers – or when the computers come to convert us – what crusades, reformations and revivals can we envision? As technology continues her unheralded march, how do we measure the weight of a computer’s soul, how do we circumscribe the robot’s supplication? With apologies to Philip K Dick, in our coming digital Church, we must ask ourselves: are androids capable of being electric sheep?